- Home

- Will Hobbs

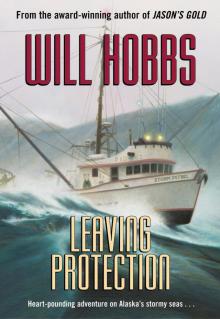

Leaving Protection

Leaving Protection Read online

Leaving Protection

Will Hobbs

to Julie Yates and her father,

George Yates

Contents

Maps

1

STRANGE, HOW IT ALL BEGAN. Silence hung over breakfast like…

2

I WAS ON MY WAY TO CRAIG, about halfway down…

3

ALL THE WAY DOWN THE dock and on the left,…

4

IT WAS ALL I COULD DO to not give up…

5

WE PULLED OUT OF CRAIG at six the next evening.

6

I HURRIED TO RETRIEVE THE upper spreads on my outside…

7

AFTER OUR AFTERNOON BREAKFAST, the fish quit biting in Veta…

8

ON FOUR AND A HALF HOURS of sleep, I was…

9

I HAD A BAD NIGHT. I couldn’t shake the image…

10

BY NOON WE WERE BACK on the outside water. Tor…

11

THE STORM PETREL WAS ON autopilot and we were plowing…

12

THE BEACH GRAVEL WAS strewn with bull kelp, beached jellyfish,…

13

THE WIND QUIT THAT NIGHT. I was so used to…

14

SALMON TROLLERS DOTTED the northern horizon. We had reached the…

15

I WOKE TO THE POSSIBILITY that king season might be…

16

IN THE WIND, THE LEADERS were quick to fly off…

17

I WENT BELOW AND THREW my clothes and boots on.

18

TOR PICKED HIMSELF UP and climbed back into the captain’s…

19

I PULLED BACK ON THE throttle and took the boat…

20

ONCE INSIDE THE BAY, I steered for the nearest troller.

Author’s Note

About the Author

Other Books by Will Hobbs

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Maps

1

STRANGE, HOW IT ALL BEGAN. Silence hung over breakfast like a spell. Somebody would make an attempt at cheerful conversation and then it would die out like a campfire built with wet wood.

I kept straining for the sound of an airplane motor. My parents and my little sister were doing the same. Maddie, who was ten, was sneaking glances like she might never see me again. My parents were in favor of my plan but they were nervous, too. If everything worked out, I was going to work on a boat fishing the outside waters.

We live in a house that goes up and down with the tides, which are huge in southeast Alaska. We live in the inside waters, in a small cove in Port Protection’s back bay. Protection is up in the northern tip of Prince of Wales Island, the biggest of the eleven hundred islands in the panhandle of Alaska, or “Southeast,” as we call it.

Port Protection is little, and by little I mean tiny. No streets, no cars, one store. We’ve got more boats than we do people.

I was born in our floathouse, and so was Maddie. The moss-covered house and the hodgepodge of cables engineered to let it ride up and down with the tides look like something Dr. Seuss thought up, but my parents get all the credit. One big cedar tree from the mountainside behind us provided all the lumber and the shingle siding. The rusty metal roof is secondhand and so are the single-pane windows, which leak lots of heat. Almost always, there’s a fire burning in the stove. Our clothes smell like woodsmoke, but they’re clean. We’re rich in a lot of ways, but money isn’t one of them.

To make some cash money, that’s why I was leaving Protection.

“You don’t have to go,” Maddie said, breaking the silence.

“But I want to,” I told her. “I’m so excited I can’t stand it. I’ve been waiting to do this for years.”

“We need you on our boat,” she insisted.

My parents, who knew better, were sitting this one out. “You guys will do fine without me for a few weeks,” I said.

“Just because you’re sixteen now, and old enough to get a deckhand license—that doesn’t mean it’s a good idea, Robbie.”

I reached over and gave my sister a hug. Just then the whole house pitched up. Books and nicknacks went flying off the shelves, and the sugar bowl sailed across the breakfast table. My father reached out and tried to grab it but missed. When it crashed to the floor, the pieces of china went everywhere.

Quick as can be, a smile replaced my mother’s alarm. “Humpback,” she announced. We ran outside onto the deck just as the behemoth’s broad back gracefully broke the surface only feet away. The whale blew out its pipes as it passed alongside our salmon troller, which was moored at the dock. The spout took its time dissolving into the morning mist.

By now we’d figured out what the whale had been doing under our feet: rubbing off barnacles against the big logs that float the house. It had happened only once before, when Maddie was too young to remember. “It’s a good sign for Robbie fishing the big water,” my sister cried. My parents nodded like they thought so, too, but it crossed my mind that it could be just the opposite. Not that I’m superstitious exactly, but when you’ve grown up around the corner from the Gulf of Alaska, you’ve seen some of what Mother Nature can do.

Right about then we heard the floatplane. A minute later Moose Borden was tipping his wing at us as he zoomed over the back bay. He landed out of sight but was soon motoring up to the house to get me. I’d been ready the day before, but I had to wait until Borden had a paying passenger to drop off at Port Protection. Moose was a family friend, and my flight was going to be free of charge.

Good-byes were brief. “Keep your eye out for a glass fishing float for me,” my sister said.

“Definitely,” I told her.

“Heads up out there on the ocean,” my father cautioned. “Stay focused.”

“You better believe I will,” I promised.

My mother flashed a confident smile. “Catch a ton of kings, Robbie.”

And that was pretty much it. I grabbed my stuff and a couple minutes later I was flying over the floathouse. My family was looking up and waving like there was no tomorrow.

2

I WAS ON MY WAY TO CRAIG, about halfway down Prince of Wales Island, fifty or so air miles. Craig is one of the major fishing towns in Southeast, and the metropolis of the island with around fourteen hundred people. It was a short hop by air taxi, and I spent it fretting. The July 1 opening of king salmon season was less than forty-eight hours away. I only hoped I hadn’t cut it too close.

My first glimpse of Craig’s harbor, out the window of the floatplane, had me doubting my chances of landing a job. The docks were crawling with fishermen, and this late in the game, skippers were unlikely to be hiring crew. But I could still get lucky.

Moose splashed down, taxied toward the floatplane dock, throttled back, then killed the motor at the precise moment that would allow the airplane’s momentum to drift it to within stepping distance of the dock.

When Moose jumped off and tied up, I was right behind him. I thanked him for the huge favor, slung my daypack onto my back, grabbed my duffel bag, and took off running.

The boat harbor was only a couple of blocks away. I slowed down as I got to the parking lot and stopped to catch my breath, feasting my eyes on the forest of masts, trolling poles, antennas, and exhaust stacks below: fishing boats, nearly all of them. I would settle for a gill-netter or a seiner, and happily pocket my wages, but catching fish with nets wasn’t really what I was after. A troller was what I was shooting for. There’s no other fishing that compares.

I started down the ramp to the docks. The tide was out, so the ramp was steep. It was busy with people going down, hands full of ge

ar and groceries, and people coming back up, hands empty.

At the bottom, I took a right on the dock’s first side branch to see what the eagles were screaming about. The commotion was coming from the lawn of a house in the lap of the marina. A dozen or so bald eagles were fighting over some fish guts someone had thrown on the grass, maybe the white-haired man looking out the picture window.

Just like our chickens back home with their scraps, the eagles were running in all directions with their prizes, fighting off the ones who had dropped theirs the moment they suspected that the other guy had a superior tangle of guts. They ran so stiff-legged, throwing their weight from side to side, it was almost comical.

Someone was watching me watch the eagles. A voice passing by my shoulder said, “It’s a dog-eat-dog world out there.” It was a woman’s voice, infectiously friendly. With a glance I recognized her as an island legend, a teacher from Craig who had fished the outside waters with her father since she was a small girl.

She paused, a plastic laundry tub full of canned goods on her hip and a boy about ten in tow. Her hair was long and jet black. Like me, she was part native—Haida, in her case. She had a big friendly smile on her face.

I was tongue-tied. Her father’s power troller, the Julie Kristine, famously named after her, was in the very next slip. “You’re not from around here,” she said.

“Port Protection,” I replied. “You’re George Yates’s daughter, right?”

“You bet,” she said with a grin.

“I saw an article about you in the Island News a couple of months ago. About how you took kids canoeing on the Thorne River.”

“Amazingly, they all got back alive. Do you homeschool, or go to school in Protection?”

“We used to homeschool, but the last three or four years I’ve been taking our motorboat in to the public school.”

“I’m glad you’re helping to keep it open. How many kids are enrolled these days?”

“Nineteen, first grade through high school.”

Her son was tugging at her sleeve. She gave him a sharp glance and he quit tugging. She patted him on the head as she explained, “Bear thinks the season will get here sooner if he gets even more excited. It’s his first king season.”

“I’ll run ahead and help Grampa,” Bear said, and took off. His mother set her things down. “So where are you headed with that duffel bag?” she asked.

When I told her about my situation, Julie was doubtful about my plans. It wasn’t so much that all the jobs had been taken, as she explained. With the price of salmon down drastically for the third straight year, crewing had become a dicey proposition. A lot of the local college and high school kids thought anything else, even working in a video store or delivering pizzas, was a better bet.

“It’s a real shame,” she said. “I put myself all the way through college crewing on my dad’s boat. Some people say kids aren’t fishing because the work is too hard, but I think it’s because they’ve done their math. Fifteen percent of the captain’s paycheck isn’t so attractive these days. Your own overhead is going to run you, let’s see, for starters, sixty dollars for your crew license.”

“I brought the money. And my ID.”

“Okay, factor in your share of the groceries, which will come out of your earnings. The season might run two weeks, and groceries are expensive. So’s the captain’s fuel, and a percentage of that might be yours.”

“I have to pay part of the fuel?”

“With some skippers you do, with some you don’t. It gets subtracted from your take, same as the food. Add it all up, you could be starting out a couple hundred dollars in the hole, maybe more. If your captain doesn’t catch many fish, you could end up owing him money.”

“You’re kidding.”

She shook her head. “I wish I was.”

“Well then,” I said, “at least there must be a lot of jobs available.”

“Not really. A lot of skippers can’t afford a deckhand. Lots of them are working alone.”

“That’s dangerous.”

“Absolutely.”

“Come on, there has to be some money to be made. The quota is decent this year, right?”

“A hundred and sixty thousand kings for Southeast, but who knows where they’re going to be? Some boats don’t get within a hundred miles of where the big numbers are being caught. The season could be over before you start making money. I’ve known it to close in six days. Look, I hate to sound so discouraging. What do you think? Do you still want to try to find a boat?”

“I don’t have a video store to work at in Protection, and there sure isn’t any work up there delivering pizzas.”

Maybe it was the way I’d said it. She laughed even though she knew it wasn’t funny. “I’ve been waiting my whole life to turn sixteen so I could do this,” I explained. “I gotta find a highliner.”

We both knew I was in the company of a highliner at that very moment. The Julie Kristine was one of those trollers known to return from the outside waters half-sunk with fish, time after time. Julie and her dad were true highliners. Not that they would use that term to describe themselves, not in a million years. It’s always the other guy who’s the highliner.

“Got any you could recommend to me?” I asked her.

“A highliner, eh? There aren’t many to begin with, and they tend to have the same person working with them year after year. Someone who knows their every move and works at least as hard as they do.”

I was thinking as fast as I could. “What about a boat from out of state?” I said. “A boat from Washington, maybe?”

“Hey, good idea. Maybe you could talk to the buyer over at Craig Fish. Ask if he knows a big-time producer who usually fishes solo.”

“I guess that would be a long shot.”

“Wait a minute,” Julie said. “I just thought of a guy who matches your description. He comes up every summer. I saw him pull in yesterday. He’s been fishing even longer than my dad. When you’re out on the drag, every time you look over at that man, he’s pulling fish.”

“Now you’re talking. This is perfect. I could work on a troller! That was what I was hoping.”

“Hey, don’t get carried away. I don’t even know this guy. All I know about him is, he catches a lot of fish. Chances are he won’t hire a deckhand. Those old-timers are set in their ways, and he’s used to fishing alone.”

“I feel lucky,” I told her. “I want to give him a try. What’s the name of my boat?”

“The Storm Petrel, out of Port Angeles, Washington.”

“Keep an eye out for me on the drag,” I said. “And thanks.”

“I’ll wave,” she said.

3

ALL THE WAY DOWN THE dock and on the left, in the last slip, that’s where I found the Storm Petrel moored. It was a salmon troller to die for, forty-five feet or so, with a fiberglass hull. She was white with green trim and immaculately maintained. As I approached I kept an eye out for my Washington State highliner.

Through the wraparound windows of the wheelhouse, I could see the little table where the skipper ate his meals, and behind it, the galley with his stove and sink. On the opposite side, behind the wheel, was his bunk. He wasn’t inside. Along the slip, I walked the length of the troller. I didn’t find him on the deck behind the wheelhouse or in the cockpit along the back of the boat. He must have walked up to the grocery store, I figured.

A highliner was worth waiting for.

I waited, got restless, then committed a cardinal sin. With a guilty glance along the dock to see if anyone was looking, I stepped over the bulwark. The hardwood trim was exquisite, with not so much as a varnish bubble showing. I walked across the Storm Petrel’s bright turquoise green deck, leaned on the hayrack, and admired the fish-cleaning cradles in the holding bins on either side of the boat. Each of the cradles—simple, V-shaped plywood devices for keeping a salmon spine-down as you clean it—had a fish gaff lying in it, at the ready. Wouldn’t that be something, to be standing in

the cockpit of a boat as splendid as this one, hauling huge kings aboard!

With another glance over my shoulder—the coast was clear—I swung down into the cockpit. My hand on a gurdy lever, I imagined I was pulling the gear up, a king salmon on every hook. I grabbed the fish gaff, leaned over the stern, and pretended I was clubbing, then gaffing, a huge king. With the king landed in the cleaning bin, at least in my imagination, I returned the gaff to the exact position where I’d found it.

No one was watching, so I snooped around a little more. Here was a small wheel, just like on my family’s boat, so you could steer from the stern as well as from inside the wheelhouse. Here was a remote station for the autopilot; we had that, too. Barely forward of the cockpit, dead center and waist high, was an enclosure of painted hardboard open only to the back, to keep a few things accessible yet out of the rain. I spotted a plastic tray full of lures. With a peek around, I reached for it. I found hootchies of various colors, their wavy plastic tentacles concealing number seven Mustad hooks that the fisherman had filed extra sharp. Off to the side, brass spoons were soaking in a bucket of Hydrotone so they wouldn’t tarnish.

I was about to put the lure tray back when something caught my eye, the dull dark plate of metal that the tray had been sitting on. It had a strange sort of emblem on it.

I set the tray aside and reached for the metal plate. Rectangular, about eight by ten—whatever it was, it was heavy. The metal was copper, badly tarnished. Or was it some kind of alloy? The emblem, under the number 13, was a two-headed eagle with its wings spread wide. The heads faced in opposite directions. I’d seen a figure like it on a totem pole once. The plate looked really old, and there was writing across the bottom in a strange alphabet.

City of Gold

City of Gold Kokopelli's Flute

Kokopelli's Flute Take Me to the River

Take Me to the River Jackie's Wild Seattle

Jackie's Wild Seattle The Maze

The Maze Ghost Canoe

Ghost Canoe Never Say Die

Never Say Die Down the Yukon

Down the Yukon Bearstone

Bearstone Beardance

Beardance Jason's Gold

Jason's Gold Far North

Far North The Big Wander

The Big Wander River Thunder

River Thunder Downriver

Downriver Go Big or Go Home

Go Big or Go Home Leaving Protection

Leaving Protection Wild Man Island

Wild Man Island