- Home

- Will Hobbs

Leaving Protection Page 2

Leaving Protection Read online

Page 2

“Looking for something?” came a voice like a thunderclap. I jumped, turned around, shrank back. Right above me, filling up the sky in an old gray halibut coat, was a very angry fisherman. My heart went to jackhammering as I set the strange metal plate back where I’d found it.

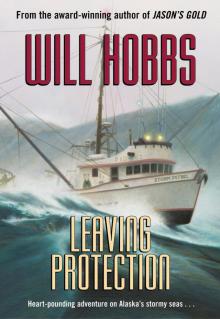

“What are you doing on my boat?” the man demanded, the captain of the Storm Petrel no doubt, big as a Sitka spruce, with a long, angular face furrowed by the weather, a full head of gray hair, and an untrimmed salt-and-pepper beard. His dark eyes, sharp as his hooks, were easy enough to read. He had me dead to rights, and he was thinking of skinning me alive.

“I’m really sorry,” I said.

He scowled at me like I was the ugliest bottom feeder he’d seen in his life. My eyes went to his massive forearms. I think of myself as plenty sturdy, but his fish-killing hands could have reached down and throttled my neck like a chicken’s.

“‘Sorry’?” he boomed.

I scrambled out of the cockpit and got the heck off his boat. On the pier, I reached for my stuff, but the fisherman stepped in front of me, blocking my way. “Where do you think you’re going?”

I took a step back. “I knew better,” I said, afraid to look into his face. “Really, I apologize. I don’t blame you for being mad.”

“You don’t blame me?”

“Just let me go.”

I watched closely to see if he was going to kill me, or have a heart attack, or what. His eyes were bulging like a red snapper’s when it’s yanked to the surface.

He was livid, but at the same time, he seemed to be wrestling to get himself under control, which I was all in favor of.

His eyes went disapprovingly to the small gold hoop on my right ear. “I want to know who you are and what you were looking for.”

All I could think of to say was the simple truth: “I was looking for a boat.”

“This one’s not for sale,” he shot back.

“I mean, I want to work on a boat,” I explained.

“You’ve got a strange way of going about it.”

“I know. I know I’ve blown it.” This sorehead was never going to let me off the hook. “I feel awful,” I said. “Especially because I didn’t want to work on just any boat, I wanted to work on yours. I got all excited about the idea, came on board, and got carried away.”

His overgrown eyebrows lifted. “Why my boat?”

“Because George Yates’s daughter recommended you.”

“Who?”

“Julie Kristine. She’s a teacher who fishes with her father every summer.”

“I don’t know her.”

“I’m not from around here. She is. Maybe you’ve seen the boat named after her.”

“I’m thinking I have. Did she send you to snoop around my boat?”

“Why would she do that?”

The captain of the Storm Petrel hesitated, cast a glance back toward the cockpit, then said nothing. He just looked me up and down, his eyes full of suspicion.

“She just recommended you,” I tried to assure him. “Like I said, she told me you’re one of the best.”

He settled down a little. “Keep talking.”

“She says you’ve got a fish-catching boat, and a fish-catching boat is what I’m looking for.”

“Didn’t she tell you I work alone?”

“She did. I just wanted to hear it from you.”

“I work alone. There, I’ve said it.”

I’d dug myself a huge hole, but maybe I would get lucky and climb out of it. He had the charm of a wolf eel, but he was a highliner, the real article.

I started pedaling as fast as I could. “My name’s Robbie Daniels,” I began. “I won’t get in your way, I won’t talk if you don’t want me to, I’ll work like you wouldn’t believe. I just want the chance to work. I’ll work as hard as you do, even harder.”

The highliner squinted at me. Maybe he was interested. I started talking even faster. “I’ll get up as soon as you do. I’ll work all the hours you do. I don’t care about breaks. I’ll do the dishes, I’ll clean fish as long as there’s daylight, I’ll do all the work down in the fish hold, I’ll take over the wheel if you want to catch a nap—”

The fisherman lifted his huge paw, indicating I should stop. “Robbie Daniels, you said your name was?”

“Yes sir.”

“Just get out of here,” the highliner said abruptly.

I can’t say I left with my head held high. I might have been relieved if I hadn’t been so disgusted. Not with him, but with myself.

4

IT WAS ALL I COULD DO to not give up right then and there. Part of me wanted to get back home to Protection as fast as possible. If I hurried, my pilot might still be over at the floatplane dock.

Moose Borden was going to think I was nuts. I could hear him saying, “How many skippers did you talk to, Robbie?”

I told myself to calm down, start over, and try again. That’s what I did. I worked it hard all around the docks. It turned out just like the teacher had thought: skippers couldn’t afford a deckhand, or they’d already hired one. Half a dozen had hired only the day before.

By four in the afternoon I was ready to give up, and I was starving. I found a chowder place nearby and ordered a halibut burger with curly fries and a chocolate malt. The place was noisy, packed with fishermen counting down the hours as they swapped tales and talked king salmon gear, the weather, and their chances. They were already dressed in their fishing jeans, Carhartts like mine. Being this close to the Super Bowl of commercial fishing in Southeast, and knowing I wasn’t going to get in on the game, there was a gnawing hunger in my gut that food couldn’t touch. When my burger arrived, I started in, but I couldn’t even taste it.

It felt like I was the only one sitting alone, but I wasn’t. Over in the far corner, an old-timer turned around and gave me a long, pained look. It was the captain of the Storm Petrel, his face as unforgiving as the ocean.

I turned my attention to my burger and my thoughts to the family friends I would be staying with that night. It was time I should be checking in with them. Too bad they didn’t know a boat I could work on; my parents had already asked.

I wanted to dump my stuff at their house so I wouldn’t have to lug it around with me. Then I’d make one last round of the boats. There had been quite a few with nobody aboard when I’d been job hunting.

Without a backward glance toward the captain of the Petrel, I left the restaurant and headed for the pay phone around the corner of the building. I’d dropped two quarters and was punching numbers when someone crowded in behind me. I looked up, and it was the captain of the Storm Petrel. “Put down that phone,” he said.

Did he think he owned me after one dumb mistake? “How come?” I said. It’s not like I hadn’t already apologized. If he wasn’t going to let it drop, I was ready to stand up for myself.

Just as a voice came over the phone, the fisherman reached out and disconnected me. “Look,” he said, his voice softening suddenly, his eyes, too, “I shouldn’t have jumped all over you the way I did.”

I was so surprised. Now it was the highliner who was apologizing, and he sounded sincere despite the rough edges. “That’s okay,” I said. “I had it coming.”

“So, you’re looking for a boat. Or did you find one?”

“No sir, I’m afraid I haven’t.”

“Grab your stuff and come back to my troller. We’ll talk about it, if you’re still interested.”

This was almost too good to be true. “Sure, let’s talk,” I said. “I don’t want to miss king season if I can help it.”

We started walking. “You were going on about what a hard worker you are,” the old-timer said on our way back along the dock. “What kind of experience you got?”

“Tons. I was raised on a salmon troller.”

“A fisherman born and raised, eh? I suppose you know all about GPS navigation, how to read the nautical charts, the Fathometer, the radar.”

“All that.”

>

He stopped in his tracks. The slightest of grins was remaking his face into a shape that was refreshingly human. “What is it you won’t do, tell me that.”

Here was my chance to let him know there was something I wanted out of this besides money. I said, “I won’t not pull the salmon.”

“Huh?”

“I mean, I want to catch fish myself, whenever I’m caught up with the cleaning and icing. If you have to work all four lines and land all the fish by yourself, I’m not interested.”

He seemed amused. “You’re pretty firm on that, I take it.”

“That’s right. I want to be conking kings and pulling as many aboard as I can.”

“Fish till your arms fall off, it sounds like.”

Finally we were talking the same language. “That’s right,” I said. “I’ve always wanted this kind of a chance. Chimes of Freedom, my family’s boat, is only twenty-eight feet long. Where we fish, there aren’t many kings. There’s nothing in the world like having a big king salmon on your hands.”

“Tell me about that,” the fisherman said. His dark eyes, green as the north Pacific a fathom below the surface, betrayed a fisherman’s fondness for the subject at hand. This was more like it.

I emptied the whole bucket: “Once you take that leader off the trolling wire and it’s just you and the king, no fishing pole, just the line in your hands and the hook in its jaw and all that power running through the line, through your hands, all the way down your spine, you feel as connected as you’re ever going to get.”

“Connected to what?” he asked.

“Connected to…everything.”

He nodded thoughtfully, then started walking along the dock again. “You drink coffee?” he asked as we reached the Storm Petrel. His tone of voice was downright civil.

Maybe I’d said the right things. Maybe he did have the need for a good deckhand. “If you got a big slug of sugar to put in it,” I said.

“So, you like a little coffee with your sugar. You must be a Turk.”

The guy was actually loosening up. “I’m not Turkish,” I said with a grin, “but I am one-eighth Tlingit, on my father’s side.”

“Did he raise you Tlingit?”

“No, and he didn’t grow up native either. I’ve learned some stuff out of books, but that hardly counts. The Tlingits are the Indians that the Russians stole southeast Alaska from.”

“The Russian fur hunters were a scurvy lot. Barbarians.”

“Hey, watch it,” I shot back. “I’m part Russian, too.”

He laughed, actually laughed, then led me onto his boat and into the wheelhouse. I was thinking about that metal plate: a Tlingit symbol over Russian words, was my guess, not that I was going to press my luck and bring it up.

“Part what else are you, then?” the highliner asked as he took two big mugs from the cup hooks above his galley stove. They were wide and squat, with traction pads to resist the pull of heavy seas in the open ocean. He set them on the rail between the stove and the little dining table. “German, English, Norwegian, and Irish,” I answered.

“What a coincidence,” he said as he poured a brew dark like old engine oil into the mugs. “Those last two, that’s me. My father was a gloomy Norseman and my ma was Irish, a tempest in a teapot. The part in me that riles easy, I blame it on her.”

I sat down at his table. As he settled in across from me, the fisherman reached for a big bottle of extra-strength Tylenol and shook out three capsules. He washed them down with coffee.

“Sounds like you’re not from Klawock, the Tlingit town,” he continued. “And we already established that you’re not from Craig.”

“I’m from way up at Port Protection. You know where that is?”

“Sure, I know Protection. I knew it from when it was just the summer fish plant and the trading post. You live along the boardwalk?”

“No, in the back bay, in a floathouse.”

“No kidding. Up and down with the tide. They ever punch in one of those logging roads?”

“Every so often there’s talk, but the locals, including my parents, like it the way it is. It would be the end of our big trees.”

“And a whole lot more. Are you a subsistence family?”

“Yep, we’re still in the hunter-gatherer stage, rounding up our food as best we can. We’ve got our shrimp pots, crab pots, greenhouse, and our salmon troller, the Chimes of Freedom. We salvage stuff and turn it into something else.”

“Self-reliance people.”

“You could say that. My parents came to Protection a long time ago to live away from the power grid.”

“You must have a generator.”

“We only use ours for backup these days. My sister hated it when she couldn’t hear the whales spouting. There’s a creek right behind us. My dad and I built a setup where the creek turns a paddle wheel on a crankshaft that works a pulley attached to an alternator.”

“Not too shabby. Can you store the juice for when you have a heavy load?”

“In a bank of eight twelve-volt batteries. The microwave especially draws a lot of juice.”

“You’re all set up, then.”

“We get by. I can’t make any money there, that’s the problem.”

“Your father’s got a salmon troller, but he doesn’t do any serious commercial fishing? Why can’t he pay you to keep working on the family boat?”

“We fish the other four species of salmon, but the only real money these days is in the kings, and we can’t get to them. Boat’s not big enough. Even when the kings are in the inside water, they’re running deeper than we can fish. Those lighter cannonballs only take the gear down fifteen fathoms, twenty at the most.”

“Wait a second, you aren’t hand trollers, are you?”

The guy was back to looking at me like I was some kind of bottom feeder. “Yep,” I admitted, “we crank our lines by hand.”

“In that case you’ve got no experience to run my power gurdies.”

“I’ve run ’em some on other people’s boats.”

“Some?” he asked skeptically.

“You’re right. I won’t get your lines up and down as fast as you, at least not at first.”

He didn’t say anything. I was about finished with my coffee, and it looked like my highliner was about finished with me. He’d only wanted to make himself feel better about the way he’d acted when he caught me on his boat. No hard feelings, have a good life.

The clock above the table said a quarter to six. Last chance to track down a few more skippers to talk to. I got up to go.

“Slow down,” the highliner said irritably. “Something you said earlier this afternoon made me think.”

“What was that?”

“It was about you doing everything in the hold. Icing the fish and all. I’ve been having some trouble with my back, quite a bit of trouble.”

I waited for him to go on.

“It’s been seizing up on me for years. It comes and goes, but I’ve always been able to work through it. Last summer it got real bad for a spell. Climbing in and out of the hold, all that stoop work down there…if it got even worse—”

“I’m your man,” I said.

“I can’t tell you how long it’s been since I had a deckhand,” he said. “And I’ve never had one that worked out.”

“This time will be different.”

“It better be. I expect you to make good on all those things you said.”

“I guarantee it.”

“Fifteen percent and half of the grub and the fuel? Is that still the way it works?”

Rather than quibble, I said, “It works for me.”

“Tor Torsen,” he said, extending his hand across the table. “Call me Tor.”

“Good deal, Tor. What time should I report tomorrow?”

“Tomorrow?” he said incredulously. “You expect to hop on at the last second, after all the prep work is done? Icing the hold and so on?”

“I didn’t mean it like that. I mean,

I was going to stay in Craig tonight with some friends of my family. That’s who I was going to call. They just moved down from Protection.”

“Hey, sleep on the boat. I aim to put you to work. We have a lot of grocery shopping to do; we could be out for a couple of weeks. And there’s leaders to rig. I suppose you know how to do that.”

“Sure, sure.”

“Call those people—be quick about it. Tell ’em you aren’t coming. Just throw your stuff aboard. I’ll be waiting when you come back.”

“Good deal,” I said, a little uncertainly. I didn’t really understand how all this had happened. I had a strange feeling, like I was being flooded by a high tide. I wished I had more time to think, but this was my big chance. I was going to have to take it or leave it.

I took it.

5

WE PULLED OUT OF CRAIG at six the next evening. I sat on the aft deck, on the big hatch lid over the fish hold, watching the harbor recede. The houses on the hill grew smaller and the clearcuts on Sunnahae Mountain grew large. After a fast-moving rain, everything was golden in the evening light.

There was no telling how long I might be out on the ocean. If king season stayed open for two weeks, Tor wasn’t going to lose time resupplying in the middle of it. The galley pantry was stocked to the gills with canned goods, plus we had four milk crates overflowing with refrigerated stuff. Like the Chimes, the Storm Petrel had no refrigerator. The fish hold was one big icebox. Push back the hatch lid and the milk crates were right there, on a tray spanning the pit.

Torsen wove his way among the outer islands for several hours. It was obvious he knew these waters as well as any local skipper. He dropped anchor in Pigeon Pass. The anchorage was in the lee of Baker Island, out of reach of the swells coming off the open ocean. My highliner lay down on his bunk behind the wheel just after nine. A couple of minutes, no more, and he was sawing logs. I hung out on the deck listening to the spouting of nearby whales, rehearsing what it would be like to run the power gurdies.

The sea swallowed the sun around ten. It was after eleven before the lights atop the masts of the surrounding trollers were shining bright. Summer days in Alaska, how they linger. Locals like me hate to waste precious daylight. Sleep is for winter, when you’re not missing anything but darkness.

City of Gold

City of Gold Kokopelli's Flute

Kokopelli's Flute Take Me to the River

Take Me to the River Jackie's Wild Seattle

Jackie's Wild Seattle The Maze

The Maze Ghost Canoe

Ghost Canoe Never Say Die

Never Say Die Down the Yukon

Down the Yukon Bearstone

Bearstone Beardance

Beardance Jason's Gold

Jason's Gold Far North

Far North The Big Wander

The Big Wander River Thunder

River Thunder Downriver

Downriver Go Big or Go Home

Go Big or Go Home Leaving Protection

Leaving Protection Wild Man Island

Wild Man Island