- Home

- Will Hobbs

Bearstone

Bearstone Read online

BEARSTONE

Books by WILL HOBBS

Changes in Latitudes

Bearstone

Downriver

The Big Wander

Beardance

Beardream

Kokopelli’s Flute

WILL HOBBS

BEARSTONE

ALADDIN PAPERBACKS

New York London Toronto Sydney

If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.”

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real locales are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

First Aladdin Paperbacks edition September 2004

Copyright © 1989 by Will Hobbs

ALADDIN PAPERBACKS

An imprint of Simon & Schuster

Children’s Publishing Division

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Also available in an Atheneum Books for Young Readers hardcover edition.

Printed in the United States of America

8 10 9 7

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Hobbs, Will.

Bearstone.

Summary: A troubled Indian boy goes to live with an elderly rancher whose caring ways help the boy become a man.

ISBN 0-689-31496-5 (hc.)

[1. Ute Indians—Fiction. 2. Indians of North America—Fiction] I. Title.

PZ7.H6524Be 1989 [Fic] 89-6641

ISBN-13:978-0-689-87071-2 (Aladdin pbk.)

ISBN-10:0-689-87071-X (Aladdin pbk.)

eISBN-13: 978-1-439-10726-3

For Jean

With special thanks to Greg, Ed, Dad, Joe, Dan, Jeff, Jean, Diane, Matt, Suzy, and Pepsi for all the Pine River memories. Thanks to Loyd for inspiration and to Mike for the story of his ride through the Window.

Cloyd stood a step from the door of the hospital room. His father was in that room. “Are you sure you have to see him in person to deliver those flowers?” the nurse asked.

“They won’t pay me unless I deliver them in person.”

Cloyd didn’t think it would work if he told her who he was. He had run away from the Ute group home in Colorado and hitched all the way to Window Rock, Arizona, to find his father. That’s where the Navajos kept the records about everyone in the whole tribe, and there he found out that yes, there was a Leeno Atcitty, and his address was listed as the Indian Health Service Hospital in Window Rock. He was a patient there.

Cloyd wondered how he might get into his father’s hospital room to see him. If he told them who he was, there would be trouble because he had run away. Then he had an idea. He used the last of his money to buy some flowers.

For years Cloyd had been asking every Navajo he happened to meet if they knew a man named Leeno Atcitty. “What does he look like?” they’d ask. Cloyd couldn’t tell them; he’d never known his father. He’d grown up without him, with only his sister and his grandmother. Cloyd knew just two things about his father—he was a Navajo, and he had disappeared after Cloyd was born. Nobody had seen him since.

When Cloyd was little, he used to talk to his sister about how badly he wanted to find his father, but she didn’t seem to need to know him at all, so he had kept his dream inside. In the year since he’d been sent away, the more lonely he became, the stronger his desire grew to find his father. Now here he was with his heart pounding, following the nurse down the long hallway to his father’s room.

The nurse stopped short of the door and said, “Why don’t you let me take the flowers in.”

Cloyd didn’t know if this was going to work. He wasn’t a good liar. He said, “I’m supposed to deliver them myself.”

“I’ve never seen you here before. Who did you say you’re working for?”

He knew he had to do something quick. Like a rabbit in the sagebrush, Cloyd was into the room.

What he saw terrified him. This wasn’t even a human being. It was more like a shriveled-up mummy attached to a bunch of tubes. One went into his nose and one went into his arm. A third came out from under the sheet. How could this be his father? Was it even alive? “What’s the matter with him?” he asked as evenly as he could.

“Have you ever heard of the expression ‘brain dead’? It means his heart and his lungs still work, but his brain is … well, dead. I tried to tell you, it’s not a pretty sight. He won’t know about the flowers.”

Cloyd had to keep talking, or the nurse would get onto him. He had to put away his terror, not show any emotion on his face. He was good at that. “How did this happen?”

“Car accident,” she said. “I don’t know any details.”

“How long has he been like this?”

“Four years.”

“Are you sure he’s Leeno Atcitty?”

“Yes, of course.”

“Where’s he from?”

“I think I heard that once … Utah, I think. Monument Valley. I wonder if this could be the man you were looking for. Nobody ever sent him flowers before.”

He knew it was his father. His father came from Monument Valley. Besides, the Navajos listed only one Leeno Atcitty.

Cloyd shrugged. “The people that ordered the flowers said he had a broken leg. Is there another Leeno Atcitty in the hospital?”

He sneaked one last look at his father. The terror returned full force. How could this … wrinkled, shrunken shell of a human being be his father? He forgot to wait for her reply. He turned and left without looking back.

“No,” she said after him. “I’m sure there isn’t…. There must have been some mistake.”

He threw the flowers in the trash.

Cloyd wanted to go home to Utah, back to White Mesa. Every mile took him farther into Colorado, farther even than Durango, where he’d spent the lonely winter in the group home. He was looking out the window of the van at the beaver dams in the creek along the highway. There weren’t any beaver dams where he came from.

His housemother didn’t speak, and he was glad. She’d said it all before. How he couldn’t go home for the summer, how she’d had this idea to put him on a ranch with an old man whose wife had died, and how much he was going to like it.

What was the old man going to be like? Cloyd wished he didn’t have to meet this Walter Landis. Why wouldn’t these people just leave him alone? All winter in the group home, through the miserable days in school, he had looked forward to going home for the summer. Now even that was being taken away from him. They were afraid his grandmother wouldn’t make him mind, that she’d let him disappear into the canyons again. Cloyd thought about how good that would be, to disappear and be free. He wanted to run away again, hitchhike home to White Mesa. When he was trying to find his father, he’d hitched all over.

“Getting close,” his housemother announced cheerfully. She pulled off the highway onto a bumpy dirt road. “Look, there’s the river, Cloyd—the Piedra River—through the trees!”

Cloyd had already noticed the river and the big pines. It was so different from the high desert back home. He rolled the window down all the way. It smelled like … pine cones.

“Walter’s is the only place north of the highway,” Susan James said. “After his place, it’s all wilderness for a hundred miles and more.”

Cloyd noticed how

she drove slowly and deliberately through the potholes, slower than she would have had to. There was only a short time left before she dropped him off. Probably she was going to tell him to behave. This rancher was an old friend of hers. There, ahead, was the gate. Cloyd thought how much he didn’t want to meet this stranger. He could hide and then hitch to Utah. He could visit his grandmother, at night when nobody would know. Then he would take off for the canyons. Nobody could find him in the canyons.

“Would you open the gate, Cloyd? Just look at that lovely orchard.”

He got out of the van and opened the gate. Through the orchard he could see open fields, sheds, and a barn. Mostly hidden behind two blue spruce trees stood a gray two-story house. Somebody’s home, not his. He could see a small figure stepping off the porch. Susan James was driving through the gate. Cloyd was supposed to close it behind her. He did, and then he bolted into the trees.

“Cloyd!” she called. “Cloyd, you come back here right now!”

He ran quickly and quietly. She was chasing him. Cloyd darted this way and that, then hid behind an enormous boulder. His heart was beating fast. He grinned; he knew she couldn’t catch him. “For crying out loud,” he heard her say.

Cloyd skittered twenty or more feet up the boulder’s sloping backside, gained its nearly flat top, and lay on his belly. He heard her tramping around in the orchard and calling with her voice raised, thinking he was long gone. She was on her way back to the van when she and the old man met, not very far from the boulder. Cloyd could hear everything they said.

“So he’s run off, has he, Susan?” the old man said. “And here I ain’t even met him yet.”

The voice sounded very old and very tired. Cloyd peeked over the edge and saw them talking. The old man’s hands were in the pockets of his striped overalls, his shoulders were slumped, his bald head bowed. Purple veins stood out on his skull. The most surprising thing about him was his size. He was little. I’m taller and bigger than he is, Cloyd realized.

“Does he do that often—run away?” the old man asked.

“Only once before, and it sure got him in a whole lot of trouble…. I just thought being out here and working with you might be good for him. A chance with school out to get away from the group home where he’s been getting into so much trouble. School has been a disaster for him.”

“Oh? Well, I wasn’t so good at school myself….”

Cloyd saw his housemother frown. “I’ll bet this is a lot worse than you ever did, Walter. He failed all seven of his classes. The school says he just won’t do the work, but I’m not sure he even knows how. He’s fourteen, but he missed four years of school back in Utah.”

“Four years! Where was he?”

“Out in the canyons, herding his grandmother’s goats. I think he’s at least half-wild.”

The old man grinned mischievously. “Now, ain’t that somethin’.”

Cloyd liked the old man’s chuckle. The rancher didn’t act like other grown-ups.

“So he was living with his grandmother?” Walter asked. “What about his parents—why isn’t he with them?”

“His mother’s dead—died when he was born. She was Ute. No one seems to know much about his father, just that he’s a Navajo. He left when she died. Cloyd’s always lived with his mother’s people. So tell me about yourself, Walter. How’ve you been doing?”

“Not worth a darn. Since Maude passed away and I sold off the cows, I haven’t even put up a hay crop.”

“But look at these beautiful peaches,” Susan James said brightly. “You can’t tell me you’re not taking care of this peach orchard.”

“It’s for her, Susan… for Maude. You know how she loved the peaches.”

Cloyd peered into the thick green foliage. Until now, he hadn’t noticed the trees around the boulder, he’d been so intent on listening. He was astonished. He never knew peach trees could grow so large, so full and lush, or set so much fruit. Peaches were treasured at White Mesa. He had always helped his grandmother harvest them, and it was a special time. But her trees couldn’t begin to compare with these. He admired the rancher for owning these trees.

“Just look at all those baby peaches,” Susan James said, pointing to branches loaded with fruit. “It amazes me that you can raise them here at all. I’ve never seen peaches at this altitude, much less in a canyon. Doesn’t the cold air settle?”

The old man had that impish grin on his face again. “That’s what makes it interesting.”

“Do you still have that gold mine you always talked about? With the price of gold going up every day, you must be getting ideas.”

The rancher sighed. “Oh, I’ve still got the Pride of the West, an’ I still believe in her as much as ever, but I’m not so sure as I used to be that I’ll ever get back there.”

Cloyd turned onto his back and studied the cliffs high on the mountain above the river canyon. In reds and whites, the cliffs seemed like a huge chunk of the desert hovering over the forests. They reminded him of home. In a moment, he realized that the boulder underneath him made a perfect fit with a huge notch in the cliffs up above. It must have fallen long ago, leaving behind a shallow cave. He felt good about his insight. He wasn’t stupid, like they thought. It was the first of June, a brilliant turquoise day, and he was out of school at last. He kind of liked the old rancher, too. I can hitchhike to Utah later, he thought. Anytime.

Sliding off the rock, Cloyd slipped through the orchard and vanished among the tall trees, then began to climb. He didn’t know he was climbing toward a treasure and a turning point. He wanted only to reach that piece of desert in the sky.

Under the cover of the big pines, Cloyd climbed the steep slope in leaps. As he climbed, the ranch buildings shrank until only their shiny metal roofs showed, and the peach orchard looked like a bright green circle with a sandy center. A herd of horses appeared in a pasture by the river. He was pleased to see that the old man had horses. He used to have a horse once.

Cloyd let his thoughts take him back to White Mesa, as they had all winter. Almost a year away from his grandmother and his sister, he’d had to live at White Mesa in his mind or wither away and become nobody. All winter in Durango as Cloyd sat in one classroom, then passed like a sleepwalker at the bell to the next, his spirit roamed the canyons with the flock. He put out of his mind now his other dream, the one he used to live for, the one that had turned into the man in the hospital bed in Window Rock. White Mesa was his whole world now.

Finally he stood atop the red-and-white sandstone cliffs. They had the same feel as the cliffs in the canyons where he used to take the goats. But he’d never seen a view like this one. This was a shining new world. To the north and east, peaks still covered with snow shone in the cloudless blue sky. He’d never seen mountains so sharp and rugged, so fierce and splendid. Below him, an eagle soared high above the old man’s field. It was a good sign.

Then he remembered his grandmother’s parting words as he left for Colorado. She told him something he’d never heard before: their band of Weminuche Utes hadn’t always lived at White Mesa. Colorado, especially the mountains above Durango, had been their home until gold was discovered there and the white men wanted them out of the way. Summers the people used to hunt and fish in the high mountains, she’d said; they knew every stream, places so out of the way that white men still hadn’t seen them. “So don’t feel bad about going to Durango,” she told him.

Cloyd regarded the distant peaks with new strength, a fierce kind of pride he’d never felt before. These were the mountains where his people used to live. Maybe he should stay at the ranch. Maybe he could follow the river all the way up to those peaks and stand atop the highest one. If he worked hard, there would be time off. Maybe the old man would let him take one of his horses.

Tucked under a high ridge, the outcrop suddenly lost the sun. He should be returning to the ranch. He wondered if his housemother had driven back to Durango with his duffel bag. Halfway down the side of the cliffs, he discovered

a ledge that might lead across them. That’s what he liked to do back in the canyon country: follow ledges across cliffs. You never knew what you might find. This one led to that shadowy cave, the notch he’d seen from the orchard. Its high, arching roof was indeed the perfect match to the backside of the boulder he’d climbed among the peach trees.

Cloyd sprang to the ledge. If he was careful, he could follow it, at least for a way. Below him the cliff fell more than a hundred feet. There was no good reason he had to get to the cave, yet he knew he would try it. The place itself was driving him on. The cliff houses in the canyons used to exert the same pull on him. He’d managed those climbs, nearly as difficult as this one, by using the natural cracks in the canyon walls and the handholds the Ancient Ones had carved. And he’d stood many times in their ancient homes like nests, which were said to be unreachable without ladders. When he reached those places, he felt good, standing alone in a good place.

The ledge narrowed to a seam. Arms spread wide, fingers splayed on the sandstone, Cloyd started across it with his face to the cliff wall. Carefully he edged sideways on the tips of his toes with his right foot gingerly exploring, then choosing new footing, the left following after, until he was nearly there. With a swoon he realized he could no longer lean into the cliff. The shape of the rock had forced his body weight out over thin air, and he was in bad trouble. Stretched tight, the tendons above his heels began to quiver, then to tremble. His strength deserted him in a rush. He paused to rest, but his legs began to shake violently.

His fingers started to go numb. He fought the panic and tried to think. He knew he had to go forward, reach the cave, and rest. He’d never make it back unless he could rest.

Cloyd breathed deeply and summoned a little strength into his legs. He started out again, more quickly than before. Shuffling the last few steps, he fell gasping onto the chalky floor of the cave.

Once he caught his breath, Cloyd looked for what he might find. It would take his mind off the return across the cliff. If this cave were back in the canyon country, he thought, it would have a ruin in it and maybe some picture writing. But it was bowl-smooth and empty, except for a large fin of sandstone broken loose from the wall and ceiling. He noticed something wedged between the wall and the fin—a shape that didn’t look quite natural. He shimmied into the dark, narrow crack until his hands closed on some kind of a bundle, and then he backed out into the light to see what it was.

City of Gold

City of Gold Kokopelli's Flute

Kokopelli's Flute Take Me to the River

Take Me to the River Jackie's Wild Seattle

Jackie's Wild Seattle The Maze

The Maze Ghost Canoe

Ghost Canoe Never Say Die

Never Say Die Down the Yukon

Down the Yukon Bearstone

Bearstone Beardance

Beardance Jason's Gold

Jason's Gold Far North

Far North The Big Wander

The Big Wander River Thunder

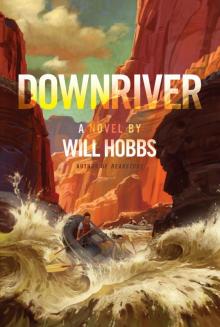

River Thunder Downriver

Downriver Go Big or Go Home

Go Big or Go Home Leaving Protection

Leaving Protection Wild Man Island

Wild Man Island