- Home

- Will Hobbs

Leaving Protection Page 7

Leaving Protection Read online

Page 7

“So, if Rezanov had lived, the history of the Northwest would have turned out all different.”

“Russian America would have become something grand, I have no doubt of that. Rezanov would have seen the possibilities far beyond the trade in sea otter pelts. Alaska wouldn’t have been sold off to the Americans, you can bank on it. Now, if you’ll excuse me, it’s past my bedtime.”

A couple minutes later, the man was snoring.

11

THE STORM PETREL WAS ON autopilot and we were plowing north at six knots in heavy seas. “Is that metallic taste in your mouth getting stronger?” I asked at breakfast.

Tor looked at me like he had no idea what I was talking about.

“Plaque Number 11?” I reminded him.

No response. After all of his storytelling the night before, the well had apparently run dry. He was making me feel like he regretted telling me about the possession plaques, the trunk, the journal, all of it. It was like he was a logger and I was a tree he was thinking about cutting down.

I didn’t know what his problem was, I only wished he didn’t have one. Trying to cheer him up, I took a different tack: “How do you wake up exactly at four every morning without an alarm clock?”

“Just do.”

“Are we dropping the gear today?”

“Likely not.”

“No time to fish? How far are we headed?”

Torsen glared at me to remind me that I was on a need-to-know basis. “Cape Cross,” he finally grunted.

I didn’t dare ask if we were going there for the fishing or for treasure hunting. Tor was reaching for his Tylenol.

By midmorning Chichagof Island was in sight, off to our right. It’s one of the biggest in Southeast, and on its windward side it has a convoluted shoreline, along with lots of timbered islands and rocky islets offshore. As we crawled the length of Chichagof, I turned to paging through Tor’s books and studying the maps. In nine days we had come almost the entire length of Alaska’s panhandle.

By evening we reached Yakobi Island, the farthest north and west of the eleven hundred islands in the Alexander Archipelago. A third of the way up its length, twenty miles or so, we anchored in a bay underneath Cape Cross. We would fish the cape the next day. It was another spot where Tor had knocked the kings dead in years past—ten thousand pounds once, from that one drag.

Along with seven other trollers, we fished it hard, fifteen hours, on July 10. The weather was foul. We caught only four kings and seven cohos. Since we’d sold on the fourth of July, we had caught a grand total of twenty-four kings and sixteen cohos. My share of the proceeds wasn’t even worth calculating. Double earnings if we found a plaque wasn’t all that exciting, either, two times zero being zero.

And so far we weren’t even looking for a plaque, despite all Tor’s talk.

Maybe he was just a con artist stringing me along with promises of a big paycheck. But why? And there was something about the way he was looking at me. I could feel him staring.

Maybe he thought I didn’t believe his story. Or just the opposite: that I knew too much about his plans. Did he think I might tell someone? I hadn’t had a chance to tell anyone, even if I’d wanted to.

Then it hit me hard. It didn’t matter what I knew—if I never had a chance to tell anyone else.

I was scaring myself. It was the end of our tenth day out, but it seemed like I’d been away a whole lot longer. Time and space and reality were bent on this boat. Was I losing the ability to distinguish between what was real and what I was imagining? I had no idea what to make of Tor Torsen.

I would have been glad if the radio had announced the closing of king season, no matter that I’d go home barely better than broke. I was tired to the bone and homesick for Port Protection.

The morning of July 11, the other trollers took off for the Fairweather Grounds to the north. There was talk on the squawk box about the fishing picking up there. I guessed we would follow suit, but I was mistaken. Instead of going out on the bow and pulling anchor, Tor went down in the engine room and brought up three items: a pick, a shovel, and a metal detector.

“You ready to dig?” he asked.

“Just tell me where,” I said awkwardly.

“You’re slow on the draw this morning.”

“I’ll have another cup of coffee. Where do we dig?”

“Out on the tip of the cape, but how close to the cape we can land, that’s going to be the problem. So far I haven’t seen a spot along the shore that will work.”

We ate breakfast, and then the captain motored deeper into the bay. It was a raw, rainy, windy day, and the surf had teeth even on the somewhat protected underbelly of the cape. At last, four or five miles in, we came to a bit of a cove. “There.” I pointed.

Tor shook his head. “It’s got a little beach now, but at high tide, it’ll be all rocks and driftpiles. Nowhere decent above the high tide line to leave the skiff.”

“Down in the fo’c’sle, next to the survival suits, you’ve got an old rope net,” I said.

“What about it?”

I explained what I had in mind, and Tor went for it. While he dropped anchor, I climbed up to the top of the wheelhouse where his little plastic landing skiff was rigged alongside the canister that stored the self-inflating life raft required by the Coast Guard. The skiff was so light, it was easy to lower it over the side. It had a pair of oars.

I placed the pick, shovel, and net inside, along with a coil of rope, my daypack, and an orange buoy that Tor used for one of his boat fenders. The daypack had enough snacks to get us through the day. For drinking water, there would be a creek every time we turned around.

“I’m going below,” Tor announced. “You want one of those survival suits, just in case?”

“Maybe so, or else I’ll never warm up after I swim.”

Tor returned with the survival suit and a high-powered rifle, which gave me the jitters. He filled his shirt pockets from a box of shells.

“There’s brownies up here,” he explained with a slow grin as I began to put on the survival suit. Just like a dog, he had a way of smelling fear. “Brown bears, huge coastal grizzlies. Not your Prince of Wales black bears.”

Torsen rowed us to shore. I was entertaining the fantasy of grabbing his rifle and tossing it into deep water. I made the landing off the bow, then collected four rocks the size of watermelons.

There was no cover on the small gravel beach. Tor huddled in the rain cradling his rifle and looking miserable. I draped my rain gear over my clothes, rubber boots, and daypack, and shoved off with the skiff.

Twenty yards offshore, I jury-rigged an anchor for the skiff with the net and the rocks. I attached the rope, lowered the anchor into twenty feet of water, then tied to the buoy. I swam back to shore and was happy for the survival suit. Only my hands and feet were freezing.

After ten days, my brain was so used to the around-the-clock rocking of the boat, now it was the land that was moving. Fast as I could in the rain, falling down twice, I got out of the survival suit and pulled on my socks and boots, jacket, raingear, and sou’wester hat in a rolling frenzy that had Torsen chuckling for the first time in days. “Let’s get off the beach,” he barked. “There’s a solid wall of devil’s club in our way. You first. You’re the Alaskan.”

12

THE BEACH GRAVEL WAS strewn with bull kelp, beached jellyfish, and broken shells of crabs and razor clams. The strip between the high tide line and the jumble of driftwood logs left by monster storms was littered with the usual pieces of Styrofoam. My eye went to a half-buried salmon flasher and a headless Barbie. Without even thinking about it—beachcombing was a lifetime habit—I kept scanning for man-made objects as I crawled over the logs to look for a way into the trees. You never knew what you might find.

A small bit of rounded green glass caught my eye. It was showing above the coarse gravel between two giant logs. I’d forgotten all about what my sister had told me at the last—to keep my eye out for a glass ball

for her, and that’s what this was. I fell to my knees and started digging with my hands. “What’s going on?” Torsen yelled from the beach. I had dropped from sight, and he sounded suspicious.

“Nothing,” I yelled back. “I found something.” I kept digging like a bear starving for clams. Japanese fishermen used to use these virtually unbreakable glass balls as floats on their fishing nets. Every two or three years my family would come across one the size of a grapefruit. I’d seen one the size of a volleyball once, but today I couldn’t believe my luck. The one I was holding in my hands was bigger than a basketball. This was the beachcombing trophy of a lifetime.

I heard Tor clambering over the logs, and now he stood high above me with his rifle. I held up the big green float; it didn’t make him smile. “For my sister,” I said, as his eyes appraised my prize.

“I’ll consider it,” he said. “I thought you were working for me. You have no idea how much I could get for that ball.”

“I don’t even want to know.”

“Cutting you in for your fifteen percent, that would be fair enough, don’t you think?”

“I don’t care how much you could sell it for,” I said stubbornly. “It’s mine, for my sister, Maddie. Finders keepers—like your plaques, Tor.”

He laughed. The way he laughed, the way he was holding the rifle, and the way he had me so far below him, between the gigantic logs: it flashed through my mind that this exact spot could be my grave.

“Leave it be for now,” Torsen ordered. The rain, gusting off the cove, was dripping through his tree-moss beard. “We’re burning daylight. I thought you had a job to do.”

For now I just wanted off, off of Torsen’s boat and out of his life. I wanted my old life back.

As I walked the high side of the drift logs looking for a way through the devil’s club, I told myself that my sister would have the glass float in the end.

There’s no part of devil’s club that doesn’t hurt. Six, eight, ten feet high, their stalks bristle with thorns. Even their foot-wide leaves are armored with stickers. I began to see a way through the jungle if I angled this way, then that.

I was less than halfway through when something in the trees behind the devil’s club started huffing and snorting. I could hear it but I couldn’t see it. I froze. It was getting closer. “Hey, bear,” I said.

The noise stopped. Everything except for my heart went dead still.

“Hey, bear. Hey, bear.” I was ready to bolt.

After a minute without hearing a thing, I thought I heard it moving away. After a couple of minutes without a sound I took a few cautious steps forward. The animal started snorting again, then gave a sharp woof.

That’s it, I thought. I’d had enough. I turned and worked my way back to the beach, but a little too fast. No wonder the side of my hand stung; it looked like a pincushion.

“What took you so long?” Tor growled as I began pulling stickers with my teeth.

“Didn’t you hear anything?”

“Not a thing.”

“Someone doesn’t want us on this island. One of those brownies, I guess.”

“Did you find a way through?”

“I think so.”

“I’ll lead, with the rifle.”

“What do you say we try again tomorrow?”

“Go through all of this again? Are you nuts?”

“I just don’t think we should shoot a bear if it isn’t necessary.”

“What are you, a tree hugger? Bear hugger? Go back and grab the pick and shovel, the metal detector, and the survival suit. Once we get through the devil’s club, we’ll hang the suit in a branch to mark our way back to this cove.”

We never saw my bear. When we didn’t even see tracks in the delicate, spongy moss on the far side of the devil’s club, Tor looked at me like I was a five-year-old who’d hollered wolf. I shrugged. I didn’t know what to think. I was remembering a native legend about forest creatures that are half animal, half human. When people drown and their bodies are never found, that’s what happens to them. Get a grip, Robbie, I told myself.

Tor hung the bright orange survival suit in a tree. “Let’s march,” he said.

I stayed close behind the man with the gun. It was slow going, especially for me, carrying all the tools. We threaded our way among fifteen-foot root discs of blown-down Sitka spruce. Atop the lengths of the fallen giants, a new generation of trees was growing from the decay. How in the world was Torsen even going to put the metal detector to work? Two hundred years had gone by, enough time for a two-hundred-foot tree to grow right on top of the plaque. Or for one of these colossal trees to fall across the spot where Number 11 was buried.

From the branches above, the ravens were talking to us, or about us, with their gurgling and popping sounds. Midafternoon, we finally left the big trees behind and picked our way through a half mile of stunted spruce, hemlock, and yellow cedar that were windblown and leaning away from the ocean.

Finally we broke out into the open. We were standing high on Cape Cross, and could see up and down the coast. In both directions, the surf was battering the rocky shore. Here and there, jets of white shot up like geysers, and the spindrift rolled up the slopes to join the cloud vapor hanging in the trees. It was another scene my mother would have loved to paint.

Torsen switched on his metal detector and started walking slowly down the spine of the cape. He kept the machine close to the ground and swept its head slowly back and forth.

“I get it,” I said. “The Russians planted the plaques out in front of where the trees grow, so it would be possible to find them.”

“On the capes,” Torsen said. “Number 12, at St. Michael’s Redoubt, was an exception.”

Torsen kept working his way down. Mostly it was smooth-scoured stone, with stunted knee-high trees growing in the crevices where pockets of soil had washed down from the forest above. Five, six times he had me dig where his metal detector did a little clicking. I produced nothing but holes.

Just before the cape’s final drop into the sea, over a pocket of dirt covered only by moss, his metal detector went off like a rattlesnake.

I started to dig. Torsen grabbed the shovel away from me. “I don’t want it damaged,” he growled.

Six inches down, his shovel struck something solid. Torsen motioned for me to back off. He sat by the hole and dug with his fingers until he exposed the tops of what looked like bricks planted upright, two rows of three bricks with something sandwiched between. Something metal, also placed upright.

Torsen pulled the bricks out and then removed a plaque. He swept its surface with his fingers. Big as life, there was the double-headed eagle, and there was the number he was expecting, Number 11.

“Unreal,” I said. “I can’t believe what I’ve just seen with my own eyes.”

“Believe it,” Tor said. With the sleeve of his raincoat, he wiped the sandy mud off the plaque, then put the plaque to his lips and kissed it. “History,” he cried out. “This is history you’re looking at here, living history. You doubted me, boy, didn’t you?”

“Did I say I did?”

“You didn’t need to. Now, let’s get out of here before dark catches us under the trees. You go in front.”

“Why’s that? You’re the one with the gun.”

“Exactly,” he said with a laugh. “I’ll cover you. You’ll scare ’em off clinking and clanking with the tools.”

None of this made any sense. Tor was giddy in a scary sort of way. All the way back, he raved about his good luck, how he had it coming after busting his hump his whole life.

He was so loud, I didn’t have to worry about surprising a bear. It was Torsen I was worried about, his gun at my back. I should have recognized the signs back in Craig. The guy was mental.

Nobody would hear the gunshot. He’d bury me right where I’d found the glass float, just scoop out a shallow grave, throw me in and shovel the sand over me, then heave a log on top.

No, the bears had too keen a sense

of smell, and they were carrion eaters. Torsen would know that. He would wrap my body in that fishing net along with those anchor rocks I had collected. Offshore, over deep water, he would drop me to the bottom of the ocean where the crabs would pick my bones clean.

A bullet could be traced to a firearm, I thought. There was a much easier way. Offshore, when no boats were in sight, he could give me a shove into the Pacific anytime he wanted. In these waters, getting away with murder would be the easiest thing in the world. “The kid fell off while I was in the wheelhouse,” Torsen would say. “I have no idea exactly when it happened. When I realized he wasn’t on the boat, I turned back and searched, but—”

Maybe the plaques weren’t finders keepers, like he claimed. Maybe he’d only hired me because I’d accidentally seen his illegal treasure. Because I might talk. I remembered how, after throwing me off his boat, he’d shown up at the pay phone just as I was about to make a call. He was all agitated about me making that call.

I had myself scared witless by the time we returned to what should have been the area where we’d first entered the forest. Once we got there, something was weird. The survival suit wasn’t on the branch where Tor had left it, or anywhere nearby.

“What’s the deal?” Tor said. “Did you put it somewhere when I wasn’t looking?”

“I was with you the whole time. What are you talking about?”

“I don’t remember,” he claimed. “Maybe that’s so, and maybe it’s not so.”

“Calm down,” I said.

“Don’t be telling me what to do.”

“Let’s look around. It must be close by.” I had a plan, if only I could get a little distance on him. It was dusk. I could hide in the rain forest, hide so well he’d have no chance of finding me by dark. When he gave up and left with the Petrel, I’d flag another fishing boat.

City of Gold

City of Gold Kokopelli's Flute

Kokopelli's Flute Take Me to the River

Take Me to the River Jackie's Wild Seattle

Jackie's Wild Seattle The Maze

The Maze Ghost Canoe

Ghost Canoe Never Say Die

Never Say Die Down the Yukon

Down the Yukon Bearstone

Bearstone Beardance

Beardance Jason's Gold

Jason's Gold Far North

Far North The Big Wander

The Big Wander River Thunder

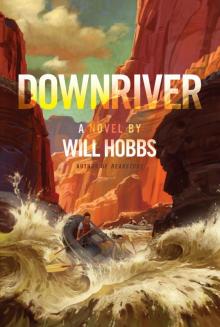

River Thunder Downriver

Downriver Go Big or Go Home

Go Big or Go Home Leaving Protection

Leaving Protection Wild Man Island

Wild Man Island