- Home

- Will Hobbs

The Maze Page 5

The Maze Read online

Page 5

Rick picked a spot to hide the canned goods under the roots of a stunted juniper, then sat down and tried to figure out what to do next. He thought about how ironic it was that he’d landed in this place. A maze was nothing new to him. He’d been trapped in one for a long, long time.

A reflected flash of light from high above on the red cliffs caught his eye: a mirror on the bird expert’s truck. The Ford was inching its way down the switchbacks. Rick had no real sense of where he stood with the mysterious “Lon Peregrino,” but he knew he needed cover. His safest option had to be staying right here, in the middle of nowhere, at least for a while.

But was it too late? Had the man already reported him? From up above, on the plateau? Rick had to know.

Lon got out of the truck and started getting himself some supper. He looked preoccupied and acted like Rick wasn’t even there. Rick felt he’d been tuned out, as if someone had hit the mute button on the TV, as if he’d been switched off for Lon’s convenience.

Cuisine for tonight, at least for Peregrino, was cold hot dogs. No buns, no mustard or relish, just hot dogs. And a green salad. Lon arranged the hot dogs and the salad on a plastic plate, then sat down on a folding chair in front of his kitchen tarp. Rick cautiously pulled up a chair next to the bearded enigma.

“So, what were you looking at up there? Birds?”

Lon seemed genuinely startled to see him. “Oh, jeez,” he said. “I’ll bet you’re hungry. Want a hot dog?”

“Thanks. Mind if I try cooking it? Heat it up in some water?”

“Suit yourself. Like I said, help yourself to whatever you want. I’m not much of a cook.”

Rick heated up some hot dogs, wrapped them in slices of bread, found some mustard and relish. He took his plate back over by Lon and sat down on the lawn chair, ready for another try at conversation. He didn’t want to start right out telling him about the men. He had to plan this, do it right.

“What kind of birds are you studying? That is what you’re doing out here, isn’t it—studying birds?” Rick thought that sounded like a safe beginning.

“Actually,” Lon answered, “I’m doing more than studying them. This is a release project. We’re reintroducing six birds to the wild. They’re condors, North American condors. Largest bird on the continent—nine-and-a-half-foot wingspan—also the most endangered. Ever heard of ’em?”

Rick tried to remember if he ever had. He shook his head.

“Ice Age survivor, nature’s most magnificent flying machine.”

There was a tone in the man’s voice of deep respect, almost of awe. Keep him talking, Rick told himself. This is going well. “‘Ice Age survivor’?” he asked. “I don’t understand what you mean.”

“I mean just that. They’re survivors from the time of the Ice Ages. The last Ice Age ended about ten thousand years ago.”

“To tell you the truth, I never understood what that was all about.”

The man studied him closely to see if he was putting him on.

Rick wasn’t faking it, or at least not very much. He was intrigued by the idea of rare vultures.

“This spot where we’re sitting wasn’t covered by glaciers,” the man who called himself Lon continued, “but a lot of North America was. The Southwest was cooler and wetter back then. More grass, more flowers, big trees where they can’t grow now—the climate supported a lot of big-time animals.”

“Like woolly mammoths,” Rick guessed. “And saber-toothed tigers.” He was remembering the visit he’d made with the Clarks to the famous tar pits in L.A.

“Bull’s-eye,” the biologist said approvingly. His deep baritone voice sounded friendly. Was the man willing to be friendly? Should he tell him now about the two men?

Lon disappeared into the commissary tent and returned with a box of cake donuts. He took one and handed the box over to Rick. “Picture giant animals moving right through here, the hunted and the hunters. Giant bison, giant ground sloths, camels, mastodons, a bear bigger than the grizzly, the dire wolf. Lots of kills, lots of carrion to get cleaned up afterward by scavengers.”

Rick was making connections. “Must have been some megavultures back then, like mega everything else.”

“That’s right. There was a megavulture, as you call it. Not all the meat eaters depended on tooth and claw. The great virtue of this one was patience. This bird was capable of soaring for a hundred, two hundred miles with hardly a beat of its wings while scanning the ground for a dinner table that was already set. All those other giant animals I mentioned are extinct. The condor was the most adaptable. It has at least a million years behind it, and it’s still around, but barely.”

Suddenly one of the condors flew above the rim, and Rick pointed. He was thrilled that he’d spotted it. The biologist hadn’t noticed.

Lon reached for his binoculars hanging from the spotting scope. “He’s up a good three hundred feet. Best flight yet! Must be M4!”

After a few seconds Lon passed the binoculars. Rick located the bird. With huge wide wings held flat and a large, ruddering tail, the “megavulture” was holding its position against the wind. At the tips of its wings, individual feathers curving slightly upward extended a long way, like fingers.

“That’s a condor you’re looking at,” the man said reverently. “They’re still around. Very few, but you’re looking at one. Their chances for survival are considered extremely remote.”

“If it’s a vulture, how come the skin isn’t red?”

“Because they’re only six months old. At five years or so, at maturity, all that gray skin on its neck and head will turn orange or yellow or a combination of the two. The adults also develop large, spectacular white patterns on the underside of their wings.”

Rick watched the huge bird come in for a landing up on the rim, on a pinnacle in front of the cliffs. “Six months old? Did I hear you right?”

“They’re just learning to fly. They were hatched in zoos out in California.”

“How come you didn’t release their parents with them, to teach ’em stuff?”

“We need the older birds for breeding, to get the population up. There aren’t any more mature condors left in the wild, none. They were down to nine individuals when the scientists decided to capture them and try to save the species by captive breeding. The adults we have now would just fly off and starve to death. They were hatched in zoos too—don’t know the first thing about locating food and a hundred other things about being a condor. These fledglings will figure it out gradually as they’re learning to fly, and they won’t fly too far away at first.”

“M4—the one we were looking at—is he something special?”

“Oh, yeah, he’s special. The day we released them—just ten days ago—he flew all the way out to that pinnacle he’s on right now. That was quite a feat for a condor fledgling. I mean, flying off the edge of a cliff with nothing but eight hundred feet of air under your wings, when you’ve only flown short bursts in a pen…that takes guts even for a juvenile, who’s naturally long on stupidity.”

Was there a trace of mockery in the man’s voice? If so, it was a good joke. And Lon was smiling.

Rick decided to seize the moment, take a chance. “You have radio contact with the outside world?” he ventured.

“Sure,” Lon replied, without sounding cagey. He pointed to a high distant plateau with a prow like a ship. “There’s a repeater over there on the Island in the Sky.”

Spill it, Rick told himself. Just ask him. But he hesitated, not wanting to make a mistake.

The biologist eyed him critically. “What is it you’re getting at?”

“Okay…did you radio me in? Like to the sheriff or something? Is somebody coming in here tomorrow to pick me up?”

This time it was the man who hesitated, studying him as he squirmed. “Not unless you want somebody to.”

Rick was confused. “I don’t, believe me.”

Silence settled in again. Rick couldn’t read this man at all. “How come you didn

’t turn me in?”

The bird biologist stroked his beard thoughtfully where it was graying, over his chin. “A guy named Ernie,” he said whimsically.

“Who’s he?”

Lon waved dismissively. “Doesn’t matter…a man I used to know. Let’s say it was on a hunch, for personal reasons.”

Once again, silence ebbed into the gulf between them.

“You’re obviously between a rock and a hard place,” the man continued finally.

“You can say that again,” Rick admitted.

“Let me just ask this. Have you hurt anybody? Is that what you’re running from?”

“It’s not that,” Rick answered quietly. “No, I didn’t hurt anybody.”

“Somebody hurt you? Put that cut on your face? Father, stepfather?”

Rick shook his head. “I don’t have one. Used to have a foster father—more than one. One of ’em taught me to drive….” With a grimace he added, “As much as I know, that is.”

The man turned his intense blue eyes on him. Rick thought he might be seeing a willingness to understand, but how could he know for sure that this man with the double identity would be fair?

“If I tell you where I came from, you’ll have to report me.”

The man with the scar thought about it. He thought about it a long time. “Can’t answer that. Keep your secret if you need to.”

“I want to stay here. I need to.”

Lon was about to say something, but Rick cut him off. “There were two guys in your camp this afternoon. I think you might be in danger.”

“What do you mean?” Lon asked quickly.

“There were two men in your camp while you were up on the cliff. They were driving an old beat-up Humvee.”

“I heard a vehicle from up above but didn’t get a look. Must have been Nuke Carlile, from the gas station in Hanksville. He comes to get water from the spring.”

“He got water, but he didn’t need water.”

At that, one of Lon’s eyebrows rose. “What do you mean?”

“I heard them talking. They didn’t know I was here. I heard a lot of things.”

Lon was interested, definitely interested. “What kind of things?”

“About you and your birds. Your visitors weren’t big fans.”

Peregrino’s eyes blazed. “If you have something to tell me, kid, spit it out. What did you hear?”

Rick told it all, slowly, carefully. The man listened intently, worrying his beard all the while. Afterward Lon grilled him on the particulars, especially about the possibility of the birds being shot or poisoned.

“The guy named Gunderson was just a hothead. Liked to talk big.”

“Like blowing my camp to kingdom come? Not a pretty picture.”

Rick nodded. “But Carlile was the guy in charge, no question. He said they weren’t going to mess with the birds, because it would bring law enforcement, like I told you. They were afraid of going to jail and all. He said they were going to pull out their stuff, whatever that meant, because you were too close and were going to stay a long time.”

The biologist looked away to the stony distances, his forehead furrowed and his blue eyes hard. “They must be pothunters,” he said finally.

“Pothunters? What’s that?”

“Looters. They pillage ancient Native American sites on public land. In this area they’re mostly after seed jars and water jars and so on—thousand-year-old pottery. Unfortunately there’s a strong black market, and that stuff’s really valuable. This whole area is rich with Fremont and Anasazi sites. Nobody knows the Maze area better than Carlile, according to the man himself—he told me so.”

“You’ve met him, I take it?”

“Just a week ago, down here, shortly after we released the birds. He informed me I’d taken ‘his’ campsite. Said he’d developed the spring behind camp a long time ago. I told him about my permit, told him anyone and everyone was welcome to come for water at any time—it’s all public land. He took exception to that term. He said, ‘You mean, government land.’”

“I didn’t mention that he made some kind of crack about you working for the government.”

“Shows what they know. I work for the Condor Project, which is supported by private donations from individuals all over the country, foundations, corporations…. Yeah, the federal government kicks in too. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service selected us to do the work. Is there anything else they might’ve said? Carlile talked about cameras. Anything else to indicate what he was looking for?”

“That was it,” Rick said, but in the moment he said it there was a twinge of doubt. There might have been another detail, but if so, it had slipped his mind.

Suddenly the biologist stood up. “I’m gonna make a call,” he said, “and then I’m gonna hit the rack. Look, you can stay here a few days. We’ll see how it goes and we’ll take it from there. Sleep in the middle tent. There’s a sleeping bag and a pillow, candles on the nightstand. Help yourself to anything in the bookcase if you feel like it. Thanks for telling me all this.”

“Were they right about you not having a gun?”

“Yeah, they were right. Say, one thing I have to warn you about, Rick, if you’re going to be around: I live out like this for a reason. I work alone by preference whenever I get the chance. I do a lot better with birds than I do with people. Sometimes I’m not that easy to be around—I work on my head a lot. So don’t expect too much.”

With that the biologist went to his truck, got in, and shut the door behind him. He raised the mike to his mouth. Rick wasn’t going to be able to hear a thing he said.

Was Lon going to say where he got his information?

Somehow he didn’t think so.

Lon had promised at least a couple of days. He had a few days to hide and rest, heal up the hammering cut in his face. Lon might let him pack some food and water, maybe even let him use the bicycle to get back to the highway.

Then what?

9

The next morning the biologist wandered off by himself to sip his coffee. Rick wanted to ask about the eagle, the one he’d discovered tethered behind the camp, but wasn’t sure how to bring it up. He waited until Lon made his way back toward the kitchen, settled into his favorite lawn chair, and started adjusting his spotting scope.

“Are you studying eagles too?” Rick asked.

“Nope, just condors,” Lon grunted.

Try again, Rick told himself. “I saw that big eagle tied to the branch behind camp. Are you going to release it?”

“Oh, so you discovered Sky. I wish I could release her, but she’s missing most of her left wing,” Lon replied grimly.

Rick felt like a fool for being a poor observer. “I didn’t notice that.”

“Hard to notice at a glance. I helped with the amputation. She’d been shot. Zoos didn’t want her. She was going to be destroyed, so I kept her.”

“How come somebody shot her?”

“Somebody was an idiot.”

Rick appreciated the directness of the answer. “I read in your bird book last night that condors got shot a lot, and poisoned too. Why do people shoot ’em? Because they’re vultures?”

“Because large, moving targets are tempting to idiots.”

“Why do they poison ’em?”

“They don’t. People poison ground squirrels and so on, the condor eats the ground squirrel….”

It was probably the pothunters, Rick thought, that accounted for Lon’s bad mood. Plus he had someone in his camp that he had to relate to, and he’d already said he liked to be alone.

“Just one more question. The book called it the California condor. Yesterday you called it the North American condor.”

Lon looked up from his scope and said sharply, “Yeah, well, if I ever write the book, it’ll get renamed. They used to live even in what’s now New York and Florida. Just because their range shrank to California in the last hundred years, that’s not a good reason to call it the California condor. What if bal

d eagles go extinct in the lower forty-eight, and they’re only left in Alaska? Should we start calling it the Alaska eagle?”

“I guess not. Sorry I asked so many questions.”

Lon wasn’t listening. He was pointing his little antenna toward different spots in the cliffs. “I’ve got a visual on everyone but M4.”

Suddenly Lon’s radio started beeping, four quick beats. The pattern kept repeating. “So there you are, M4. He’s out of sight, all right. Looks like he roosted in the cove north of where the cliff turns the corner.”

“You got transmitters on the birds?”

“So we can track ’em with radiotelemetry. There’s one transmitter on the wing, along with the tag, and one on the tail. M4’s tail transmitter went out on me and I had to replace it. He’s awful happy to be out of that pen.”

“What pen?”

Lon pointed high above. Rick was surprised to see a structure up there, thirty or forty feet back on the slope from the edge of the cliff, that he’d completely overlooked. It was a large pen, very well camouflaged, with a chain-link fence around it and a roof of camouflage netting. At the back of the pen sat a squat makeshift shelter of plywood painted rusty red like the cliffs.

“The birds were in there for six weeks before we released them,” Lon commented. “To get ’em used to their new environment. They’d get so excited seeing the ravens and eagles flying by….”

“So how’d you recapture that M4?”

“With a big net. I released him again last evening right before I drove back down. I hope he behaves himself. I’m not too happy about him roosting last night away from the others.”

“How come?”

“They’re supposed to be forming a flock. It’s crucial for their survival. Funny about M4. The biologists at the L.A. Zoo, where he was hatched, told me he’s been a maverick right along—never socialized much with the other juveniles. They thought I might get some unpredictable behavior out of him.”

“You oughta call him Maverick instead of M4.”

“We don’t give ’em those kinds of names.”

Rick was surprised at the bite in the man’s reaction. He’d said it only in jest. “How come?” he ventured.

City of Gold

City of Gold Kokopelli's Flute

Kokopelli's Flute Take Me to the River

Take Me to the River Jackie's Wild Seattle

Jackie's Wild Seattle The Maze

The Maze Ghost Canoe

Ghost Canoe Never Say Die

Never Say Die Down the Yukon

Down the Yukon Bearstone

Bearstone Beardance

Beardance Jason's Gold

Jason's Gold Far North

Far North The Big Wander

The Big Wander River Thunder

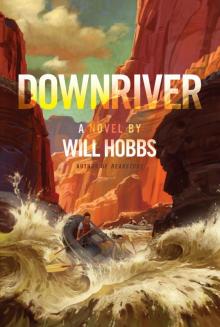

River Thunder Downriver

Downriver Go Big or Go Home

Go Big or Go Home Leaving Protection

Leaving Protection Wild Man Island

Wild Man Island