- Home

- Will Hobbs

Far North Page 12

Far North Read online

Page 12

We were stopped. Unless we wanted to try crossing on the ice bridge.

I looked downriver. If we got past this place, it was good walking as far as I could see. We approached the ice bridge and took a closer look. It was about fifty feet across and about ten to twenty feet wide, with ice shelves extending to the shores on either side.

“What do you think?” I asked Raymond. “It looks to me like it should hold us….”

Raymond kept studying the bridge. “Could we build a raft and get across here? There’s that driftpile we just passed.”

“We don’t have any parachute cord, except for the pull-rope on the toboggan, and that sure wouldn’t do it. I don’t know, maybe we could tear some of our stuff into strips to tie the logs together.”

“I don’t know either,” Raymond said slowly. “The water’s so fast…. Even if we could patch together some kind of raft tomorrow, we’d have to launch it just past the ice bridge, and from there it’s such a short distance on the water—fifty meters maybe? Then the raft would crash against the cliff at the bottom, and we’d be scrambling to get out on the ice. What if the ice down there wouldn’t hold us?”

“It’ll all be happening real fast,” I said. “That’s for sure.”

“It’s getting so late,” Raymond said, looking around. “I think fooling with a raft would be riskier than the ice bridge. We sure could waste a lot of time and wreck our stuff trying it.”

Dropping the packsack to the ground, I took off my parka and cap, my outer mitts, and then my gloves, and tucked them under the lashing on the toboggan. I started for the ice bridge. “I’ll test it first without all this stuff on.”

“Careful, Gabe.”

I took a few steps onto the ice bridge. “So far, so good,” I said. “I think it’s okay.”

“Are you sure?” I heard from behind me.

“Slow and easy,” I said, taking a few more steps. I glanced back and saw Raymond there watching intently.

Halfway across, with no warning, the ice broke with a sudden crack. I spun around, trying to get back to safety, but the big middle piece of the bridge under me slumped and broke free into the river. As I struggled for balance, the mass of ice started floating downriver with me on it. I looked over and saw Raymond on the shore, saw the shock on his face. Then I looked downstream and realized exactly what was going to happen. If I floated past that cliff on the right, Raymond couldn’t possibly reach me. Just as I realized I was going to have to swim for it, the ice underneath me rolled and I was pitched into the water.

Now you’ve done it, I thought. The shock of the cold water squeezed all the breath out of my lungs. I caught a glimpse of Raymond running along the bank. All encumbered by my heavy clothes and boots, I swam as best I could for the shore. I had to get to the shore before the cliff or I was dead.

I concentrated on Raymond’s face inside that circle of fur on his parka ruff. The wall was coming up fast. I swam with all the strength I had left, fighting the clothes and the boots. I thought I’d lost, but his arm reached out and yanked me out of the water and onto the ice.

“Get up!” he was yelling.

Get up…? I couldn’t even breathe. He stood me up, and my clothes stiffened just that fast. He hustled me along the shore, stopping only to pull on my parka, mitts, and cap. “We need fire!” he shouted, and started yanking the toboggan upriver. “We got to get back to that driftpile!”

I ran alongside thinking, Now you’ve done it! Now you’ve done it! I kept stumbling forward encased in my ice-hardened clothes, losing the feeling in my arms and legs. I could see the driftpile now in the dimming twilight. All pumped up with adrenaline, I ran ahead of Raymond.

When we got to the driftpile I kept running back and forth, just trying to keep moving. I was aware of Raymond gathering kindling; I saw him take shredded birchbark out of his pocket. I saw the shower of sparks from his fire starter. I watched his kindling catch, I rushed over, he pushed me back. He was adding more sticks, babying his fire. I was standing there frozen as a post, brain frozen, too. Raymond turned to the toboggan, freed the tarp, threw the spare clothes on it, including Johnny Raven’s moccasins.

The wind was fanning the fire into the heart of the driftpile. It was dry wood, and it went up fast. I stood close, too close—Raymond yelled at me to get back, and he helped me strip off my wet clothes.

The driftpile was becoming an inferno of heat. Within another five minutes I was flash-cooked. I changed into dry clothes, pulled on Johnny’s moccasins. The flames soared twenty, thirty feet high, pushing us farther and farther back and lighting up the canyon walls hundreds of feet above.

The danger was over, no damage done. Raymond nodded toward the bonfire. “It’s not a hot spring, but same idea.”

“You saved my life,” I said.

Raymond waved me off. “Oh, I just didn’t want to go back to Deadmen Valley by myself.”

In the morning we started back to the cabin. We were beaten, quiet as the canyon itself and filled with dread. It warmed up and began to snow about midday. By the next morning, three feet of snow had fallen. We took turns breaking trail and muscling the toboggan. My ribs started aching again. My mind drifted away from the effort and the tedium of lifting one snowshoe high, then the next, while pulling the toboggan. I figured out that the brothers who ended up headless back in 1908 probably had tried to escape down the river, just like we had, and they’d been turned back to Deadmen Valley, just like we had.

The return trip took us four days, slogging through the deep snow. At last the cabin came into sight and we trudged the last hundred yards, completely spent. I took off my snowshoes, unlatched the cabin door, and was nearly inside when I detected a quick movement in the back of the cabin. I caught a glimpse of wreckage and became aware of a strong, repulsive smell as my eyes found my danger: in a back corner behind sections of stovepipe and the upended table crouched a dark, heavily furred animal I’d never seen before in my life, about the size of a small bear. Its beady eyes were locked on mine. Then it bared its teeth.

Suddenly the cabin erupted with a vicious, snarling, utterly ferocious growl. Just then Raymond grabbed my parka and yanked me back, yelling, “Wolverine!”

Raymond pulled me back outside through the open door, shouting, “He’ll tear your face off!”

Barely behind us, the wolverine shot out the door. It ran halfway across the clearing, then stopped and looked back at us, still growling. I got a good look at the long front claws and powerful jaws. “They’re not that big,” Raymond said, “but even grizzlies leave ’em alone.”

In another moment the nasty-tempered, low-slung little beast loped off into the forest with a strange, bounding gait.

“How’d he get in?” I wondered aloud.

We stepped back inside the cabin. The place smelled rank, worse than musky. My question was answered as I looked up to see a hole in the roof where the wolverine had torn out the roof jack and knocked the stovepipe apart.

Just about everything we’d left behind was in tatters. Raymond reached for Johnny’s drum, which had been slashed into shreds.

16

IT WAS ONE HUNDRED and ten degrees warmer inside the cabin than outside. It was the seventh of January. Outside, trees were splitting open from the extreme cold, making a sound like gunshots. My breath made a crackling sound when it hit the air. The cold had Deadmen Valley in its grip, and its grip felt crushing and malicious. Fifty degrees below zero, midday, yet we had to go out and make firewood. Fifty below felt to me about twice as cold as twenty below, much more dense and much more penetrating. It hushed the land, took the breath out of it and us too. It poured right through all the layers we were wearing and into our bones.

Yet we were thinking about leaving the warmth of the cabin.

One of those army boxes stuffed full of beaver meat, that was all we had left. It won’t be much longer until it’s over, I thought. It was Raymond who brought up the Yukon. He said, “Johnny’s letter said the mountain Dene used

to spend the winter over on the Yukon side of these mountains.”

“What are you getting at?” I asked.

“They spent the winter over there because the animals leave this side and go over there. The people had to follow the animals.”

“That makes sense,” I murmured.

“Back when we were camped above the falls, Johnny told us there wouldn’t be game down here. He knew they all leave. I think his letter tells us the only thing we can do now.”

“You mean hike to the Yukon?”

“We have two rifle shells. We could get a moose over there if we’re lucky.”

“Where is the Yukon?”

“To the west,” he said. “Over those mountains. When we get a moose, we’ll make a brush teepee right there and spend the rest of the winter. One moose would get us through till breakup. The Beaver River is over there on the Yukon side—it flows into the Liard. With the moose hide, we could make enough babiche to lash together a raft and float all the way down to Nahanni Butte.”

A blizzard pinned us in the cabin for the next four days, but we needed the time to get ready for the cold that Raymond said was yet to come. With needles and an awl from the sewing kit and fishing line from the tackle box, but mostly with determination, Raymond put together a pair of huge beaver-fur mitts for himself from the pelts Johnny had tanned, several of which had survived the wolverine rampage.

While the snow fell, I made hooded face masks for both of us from Johnny’s red blanket, with openings for eyes, nose, and mouth. Whenever a lull in the storm came along, I went out on the snowshoes and rounded up birchbark for tinder in case we couldn’t find any where we were going.

Finally the storm was over. Pulling my cap down over my ears, I joined Raymond outside and latched the door behind me. Deadmen Valley, cloaked with deep snow, lay breathless and still. The cottonwoods along the river were all rimmed with frost, and they looked like ghosts of trees. The temperature was back up to twenty-five degrees below zero. We shoed up; I pulled on my big mitts over my gloves and stepped inside the sled’s pull-rope. Raymond led, carrying the packsack and breaking trail. I threw my weight against the rope and we took off, this time without looking back. We walked into utter silence, and the silence closed behind us as we passed.

We’d decided to stay out of the streambeds as much as we could, in order to avoid the places where overflow could be hiding, where the water down in the streambed had burst up through the ice and lay hidden as slush below the snow. We were going to try to escape the valley by climbing directly for the gap between the bald mountain and its nearest neighbor to the southwest—everything else was too straight up and down. We had to hope that the gap would lead us over the mountains and into the Yukon, where the moose winter. As I trudged forward I kept saying to myself, “One moose, that’s all we need. One moose. Raymond’s moose.”

The new snow had no crust and no bottom to it. Trading off with the toboggan, we waded through it, lifting our legs high to raise the tips of our snowshoes. It cost us a huge expenditure of energy. The temperature dropped, and the trees once again started going off like pistol shots. Despite all the protection, my feet ached with the cold, and my fingers too. The wind began to blow, searing our chins and noses, so they burned and went numb. We stopped and pulled on our masks. I envied the small animals who’d left their tracks atop the snow: squirrels and snowshoe hares as well as the marten, fox, and lynx that were stalking them.

We made our camp on a ridge several thousand feet above the floor of the valley and halfway to the bald mountain. The wind died away and the first stars came out, and with them the northern lights, spiraling around and waving their neon tentacles. Though we were exhausted and dehydrated, we built a low lean-to, floored it with spruce boughs, covered it with the blue tarp, and heaped snow on top, using our snowshoes for shovels. The prospect of a fire’s warmth kept us going, along with the thought of something hot to eat and the chance to melt snow and produce all the water we could drink. The only water storage we had during the day was one liter each in our water bottles, which we carried inside our parkas so it wouldn’t freeze.

The wind blew hard all night, but we discovered in the morning that it had done us a favor, crusting the snow into slabs that mostly supported our snowshoes on top of the snowpack. We kept climbing, searing our lungs, climbing, taking turns with the toboggan.

When we stopped to look back, we could see the Nahanni snaking through the entire expanse of Deadmen Valley between the upper and lower canyons. The river was frozen and white except for that one small patch of open water that even now refused to freeze. Across the river the valley speared up against a world of peaks pure white above the timberline. I said to Raymond, “I can’t believe where we are.”

“Where we are in the middle of the winter,” he replied. “I never would’ve believed this in a million years. Only the old people like Johnny ever saw this in the winter.”

“It’s amazing they could survive.”

“They say our people have been living here for thousands of years. Before rifles, before modern clothes, before hardly anything. They had to know everything about the land.”

“You know more than you think, Raymond.”

He spit, and the spit froze before it reached the ground. “I don’t know anything. I was starting to learn stuff out on the trapline with my dad, but after I was about ten I quit going out with him.”

At the end of the day we made camp at timberline, and the following morning we passed through the gap of the shoulder of the bald mountain. That mountain turned out to be only a buttress on the rim of a vast plateau above the treeline. At ten-thirty in the morning the sun rose brilliant and blinding, the first time we’d laid eyes on it in weeks. We’d climbed so high we were able to enjoy the sun for several hours as it crept toward our Yukon divide to the southwest.

We followed the edge of the plateau, using the compass when we couldn’t use the sun. Before long we were able to take off our snowshoes. Up here, with no tree cover, the wind had blown most of the snow away, leaving no more than a couple of hardened inches.

Within a few miles we came across a place where animals had dug in the snow to get at the grass. “Dall sheep,” Raymond said. The rest of the day we kept seeing their tracks, finding their droppings and the places they’d scratched in the snow to expose the grass. “Looks like they were here not so long ago,” Raymond said.

“Do you think we should try to get a sheep?” I asked.

“Not enough meat. We’ve got to get a moose.”

We camped in a dark finger of timber that reached up into the plateau. It took us an hour to find enough firewood. Then we dug snow where it had drifted so we could melt it for drinking water. After we got some hot water into us we cooked our supper. In the extreme cold, we’d gone from one meal a day to two. It was nearly the dark of the moon, yet we could still get around by the light of an infinity of stars reflecting off the snow. The aurora, bright overhead, seemed to be dancing a figure eight around the Big Dipper and the North Star. I realized that I hadn’t seen the contrail of a single jet across the sky for months.

I tried to go to sleep, but sleep never came easily with the cold seeping through the sleeping bag and all the layers of my clothing as if it were a liquid. I was looking at Orion the Hunter and I was thinking of Johnny. Suddenly wolves broke loose in a wavering chorus. Their howling seemed to come right out of the black spaces between the stars. Thinking about what was to come, I felt scared, really scared. The howling kept up, and seemed to strike the same inhuman chord as the subarctic night.

Over the course of the endless night I saw the high, transparent cirrus clouds race under a sliver of a moon, felt the wind kicking up, saw the thicker clouds come in and snuff out the moon altogether. The snow began to fall even before the morning twilight. Fortunately, we were sheltered by the stunted trees around us, but still, the swirling winds were blowing some of the stinging snow into our lean-to.

When twilight arrive

d, the storm only intensified. “Could be a blizzard,” Raymond said.

That’s exactly what it turned out to be, but a better word for it was misery. All that time, in the teeth of the storm, we had to keep scavenging for any kind of wood that would burn. Without the trees, stunted and pitiful as they were, we would’ve been dead. Our fire seemed to do so little to warm us. But we had to keep melting snow for water, and we had to eat. Our meat was going fast.

I kept track of the days on my watch. The fourteenth of January gave way to the fifteenth and the sixteenth. Out on the plateau, just a few feet away from the trees, it was an all-white world without references of any kind. Midday on the sixteenth, the sun came out. “Think we should go for it?” I asked, all out of patience, but Raymond shook his head. “If there’s more coming,” he said, “and it catches us out in the open, we might not even be able to see each other.”

In another hour the storm was back. If and when we got going again, I didn’t really believe we were going to get a moose. We’d just be slogging our way to oblivion.

The blizzard lasted another day. When we finally started out, I put on a good face. “Let’s go find your moose!” I said to Raymond. The look he gave me didn’t exactly echo my pretended optimism. Though the new snow was crusted and forgiving for snowshoes, both of us seemed to be drained of the mental stamina it would take to keep going. We were following the rim of the plateau west and keeping our bearings on the divide in the distance, but it never seemed to get any closer. I felt like a walking dead man, all out of hope and going on reflex. Finally Raymond quit walking, slumped on the toboggan. “I can’t do this,” he said. “It’s pointless.”

“Don’t worry, Raymond,” I said. “You’ll find the moose.”

With his heavy mitt, he swiped at the ice buildup around the mouth-hole of his mask. “I’m not Johnny Raven!” he cried out.

City of Gold

City of Gold Kokopelli's Flute

Kokopelli's Flute Take Me to the River

Take Me to the River Jackie's Wild Seattle

Jackie's Wild Seattle The Maze

The Maze Ghost Canoe

Ghost Canoe Never Say Die

Never Say Die Down the Yukon

Down the Yukon Bearstone

Bearstone Beardance

Beardance Jason's Gold

Jason's Gold Far North

Far North The Big Wander

The Big Wander River Thunder

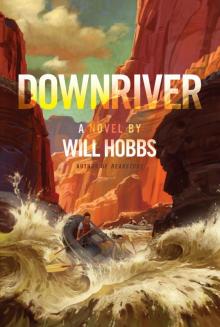

River Thunder Downriver

Downriver Go Big or Go Home

Go Big or Go Home Leaving Protection

Leaving Protection Wild Man Island

Wild Man Island