- Home

- Will Hobbs

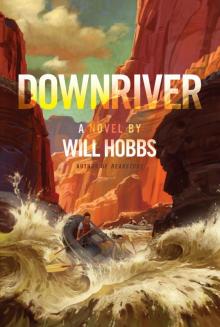

Downriver Page 12

Downriver Read online

Page 12

Blame it on me, I thought. That’s not going to help anything, Troy.

A few seconds went by, with everybody watching Troy and waiting, as we drifted even closer to the brink. What was he waiting for? Panic ripped through us as it appeared we might lose the chance to get to shore, and drift over the edge without even scouting. “Right side!” Troy yelled at last. “Tie up!”

I stumbled around among the boulders and tied off our bowline. I looked up from another pair of hands on another rope to see Star’s face, numb and blue. “So much for Jessie’s camp on the right side,” Troy was announcing sarcastically. I couldn’t believe he was doing that. Everybody kind of looked away. It was embarrassing. It was all I could do to keep from calling him out about it right there—I was thinking, if I let him get away with it now, it’s going to get worse. “Let’s think about what we’re going to do, Troy,” I suggested instead.

“Scout the rapid, I guess. We got sucked into this because of that river guide of yours.”

I couldn’t take it anymore. “Look, Troy, it’s not my fault, okay? Probably there used to be a beach here and they washed it away, jerking the river up and down all the time with their stupid dam.”

In silence we picked our way through the slick boulders on the right side, to the brink, to take a look at Horn Creek Rapid. It was simply terrifying. A short big drop with teeth, the top was studded with rocks, which funneled the only passable water into an explosive fall and chaos below—huge waves recoiling on themselves, waves attacking from both sides, and deep, boiling suckholes. “Ten-plus,” Rita rasped.

Freddy asked, “What does the guide say about camps downstream?”

I was so scared, teeth chattering too, that I didn’t even realize I had the guide in my hand or that he was talking to me. “Jessie, could I see the map?”

He turned a page over and scanned downstream. “What are you looking for?” I asked.

“Camps downstream.”

“You don’t really think we can run this tonight, do you?”

“If we do, I’d like to know if there’s any camps coming up, any beaches where we could recover if we have trouble.”

Adam and Pug were looking over Freddy’s shoulder. “There’s a small camp, theoretically, about a mile down,” Adam said. “And another theoretical small camp a mile after that, and then comes Granite Rapid, which is either an eight or a nine.”

“Would you guys hurry up and decide what you’re doing?” Rita said. “It’s going to get dark, or haven’t you noticed?”

“Lemme see that thing,” Troy said, almost shouting over the roar of the rapid. He was standing atop the highest boulder, and Adam handed the river guide up to him.

In one swift motion Troy tossed the guide out into the current streaming toward the lip of the rapid. Disbelieving, helpless, we watched it float over the brink and disappear in the white water.

We were stunned. No one said a word. No one could have thought of such an act. I couldn’t begin to calculate what the loss might mean, but I felt sick to my stomach. We were all looking at each other, totally bewildered, and sneaking glances at Troy, whose eyes were locked on the rapid. I looked back to Freddy, but he’d turned inward.

Troy, I thought, I don’t really know you at all.

I can’t remember ever being more scared than I was at that moment.

Then Troy spun around. His eyes were flickering. “We were doing a lot better without that thing,” he said. “We never assumed anything. We used our own resources.”

No one wanted to counter him. He was burning up with energy. We were all shivering and shaking. Freddy scrambled to the top of a boulder and studied the rapid. “Hey, whadda we do, Troy?” Rita said, jogging in place and hugging her sides. “Just tell us what to do.”

“Run it.”

“I have a bad feeling about this one . . . ,” Adam said.

It was spooky, hearing these sentiments from Adam. He’d do anything.

“We’re gonna flip,” Pug concluded.

“Don’t say that,” Star objected, practically sobbing.

Rita stuck her face in Star’s. “We’re only gonna die. How’s that for imaging?”

“Cut it out, everybody,” Troy said. “Freddy, what do you think? If we can run it, it would be stupid to huddle in these rocks all night long.”

“It could be raining in a few hours,” Freddy said. “Somebody might get sick. I think we can run it, but we better go quick and find camp before it gets dark.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I pointed to that ugly rapid and practically screamed at the two of them. “Look at it, will you! Are you guys out of your minds? What if both boats flip? Who’s going to live through the night?”

“Great,” Troy said. “Get hysterical, Jessie.”

There was no sense appealing to him. “Freddy,” I pleaded, “I’m not hysterical, I’m trying to be rational.”

“Come up here,” he said, and extended his hand. I let him pull me up beside him on the boulder. “It’s not as bad as it looks, really. We stay on the inside of the tongue as we enter, and then, look, there’s good water moving through all the way down. We stay on that line—no trouble.”

I could begin to see the route. “Are you sure . . . ?”

“This water level’s okay. We aren’t going to flip.”

“You guarantee it?”

He smiled and rolled his eyes. “No guarantee.”

Troy got everybody up on the rocks and pointed out the run that he and Freddy saw, talked strategy, and then we all scrambled, slipping and sliding, through the mossy rocks back to the boats. Shaking with the cold, I tugged at the cinches of my life jacket and tightened them up as much as I could. Star was struggling to do the same, but her fingers wouldn’t cooperate. “Here, Star,” I said, and helped her out. “Good luck,” I whispered.

“Let’s go, Jessie,” Troy called nervously. “I want you to ride as far forward as you can, and hold that front end down.” He was already in his seat and had the oars in his hands.

Despite all my misgivings I was stumbling around in the rocks, untying the bowline, hearing and seeing and feeling everything through a numbing fog. I couldn’t have felt any less in focus. Is this how it happens?

“Ready, Freddy?” Troy was saying.

“Just a sec.”

Freddy was rigging a piece of rope from one side of the paddle raft, underneath, to the other side. “In case we flip,” he was saying to the others, “don’t get separated from the raft. Hang on to the chicken line, then pull yourself up this rope and get onto the bottom of the boat.”

“Should we rig one of those?” I asked Troy.

“Forget it,” he said. “We’re losing time. We aren’t going to flip, Jessie. Now get in the boat, will you?”

I did. I got in the boat, stowed the bowline, and looked back for Star. She gave me a little wave. “Hang on to those paddles, no matter what,” Freddy was telling them. “We can’t afford to lose one.”

Troy was rowing out into the current. I moved forward in the boat, and spread-eagled my weight against the very front. I tried to wedge my legs into the cracks where the tubes met the floor. Only my face projected above the level of the tubes—there was no way I was going to get blown out of the boat by a big wave. The roar of the rapid intensified, the current picked up. Behind us I heard Adam and Pug chanting, “Horn Creek! Horn Creek! Horn Creek!”

“Hang on, babe,” Troy said under his breath, and I felt the boat dropping, dropping, dropping. I couldn’t see a thing with all the water pouring over me. The boat filled, just that fast. As the boat bucked and pitched with the pounding, I wondered if I was going to float out of it. I struggled to plant my legs, but just as quickly as it had all happened, it was over, and Troy was yelling, “Bail! Bail!”

I pitched two buckets of water out as Troy struggled in the turbulence to keep the boat off the dark cliff walls, and then I glanced back to check on the paddle raft. “They made it!” I yelled. “Troy, they

made it!”

“O ye of little faith,” Troy chided.

I bailed and bailed. “That was incredible, Troy! You were awesome! They’re all in the boat too—no swimmers!”

“What’d I tell you, Jessie? Now let’s find camp.”

If I’d never been so scared in my life, I’d certainly never been as relieved.

We found our small camp on the left, a little beach shining in the gloom like a beacon, right where it was supposed to be. Thank goodness it was there: A couple of more minutes on the river and we would have had to run by flashlights.

It was quickly agreed there’d be no dinner this night. Breaking out our warm clothes and putting up tents would about do it for the day. Who cared if we were hungry and freezing—we were alive.

After a while we were all sitting around the gas lantern in a tight circle, warming our hands over the exhaust fumes and rehashing our near-death experience. Everybody had a different slant on it, but Adam, bounding quickly back into form, provided the tour de force of the evening. “Great moments in history!” he shouted, and leaped to his feet. Dancing among the rocks, his face coming in and out of the light cast by the lantern, he would announce a name and then strike a pose, as if he were a statue in a wax museum. “David slaying Goliath with a little rock! . . . Ulysses on the john, thinking up the Trojan horse trick! . . . Caesar assassinated in the senate! . . . King Arthur pulling the sword from the stone! . . . Leonardo opening his first box of crayons! . . . Napoleon attempting to free his hand from his vest! . . . Washington standing up in a boat! . . . And, ladies and gentlemen, and, the newly minted Greatest Historical Moment of All Time . . . Troy throws the mile-by-mile guide into the Colorado River!”

Adam mimicked Troy’s body language at that fateful moment with uncanny perfection: He took the invisible guide in his hand, and with that Troy-like look of disdain, reenacted the infamous toss and froze halfway through the follow-through, to the howling cheers of his delighted audience.

Troy was laughing along with the rest of us. Adam, I thought, you’ve made the tension go away, you’ve defused the anger. I can see what you’re doing, what you’re telling everybody: Lighten up—what’s done is done. It’s time to come back together; our survival depends on it.

Rita wasn’t exactly on my wavelength. Brash as ever, she up and said, “Hey, Troy, what is it with maps? You have a map phobia or something? I never heard of that one.”

“What do you mean?” Troy said defensively.

“Seriously. Remember back on Storm King? You wouldn’t look at the map.”

True, I thought. Why is that?

• • •

As the moon rose, a ghostly half-moon obscured by the clouds, Troy and I sat by the river, holding hands and talking quietly. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I guess I was stressed out.”

“So was I,” I said. “We have to remember not to turn on each other—when the going gets tough, remember we care about each other, yes?” I squeezed his hand.

“And you’ll stick with me, okay? That’s all I ask.”

I said I would, but as I said good night and headed for my tent I was more than vaguely uncomfortable. I would try, but the events of this day would not be so easily forgotten, nor the feeling I experienced as he took the river guide out of my hands. I’d felt I was looking into the face of a stranger. Would I ever fully trust him again?

I joined Star in the tent. She was putting away her Tarot cards. In the light of the candle her face looked ashen, and though she looked away, there was no disguising her distress. “What is it, Star?” I whispered. “Did you just see a ghost, or what?”

“Sort of . . . ,” she whispered. “I can’t tell you.”

“But Star, what’s the matter? I really feel the worst is behind us, don’t you?”

She wasn’t going to tell me what it was, but I begged and pleaded with her. It was spooky. Her eyes were going glassy on me.

“Star,” I whispered, “if you care about me at all . . .”

She struggled, and then she said, “I do, Jessie. If you promise to listen to what I say and not take it wrong, I’ll tell you. I wouldn’t tell anyone else in the whole world, but I’ll tell you.”

She bit her lip, and then she turned one of the cards faceup. I gasped. It was the Grim Reaper astride a white horse.

“Listen, Jessie, don’t say anything, you promised to listen. Death is not to be feared, death is only a transition to another realm of existence, and all of us will die one day. You know that.”

“Yes, I can accept that, as long as it’s at a ripe old age for both of us.”

An ethereal smile played at her lips, and her eyes—they seemed to be looking through and past me. She was floating away; she’d never seemed as loosely tied down.

I took her slender forearm by the wrist. “Star,” I whispered, “what question did you ask?”

“I asked if I was going to live through this trip.”

“Star, that’s not a fair question!”

“Oh? Why not?”

“It’s self-fulfilling. It’s like a death wish. You’re the one who always says, if you think negatively, you’ll produce a negative result, right?”

“I didn’t ask if I was going to die on this trip, I asked if I was going to be alive at the end. That’s positive.”

“That’s voodoo, Star. I’m sorry, but that’s all it is. There’s so much pudding in your head, you can’t think straight.”

Star bowed her head. She wasn’t going to defend herself.

“So now you have this curse on your head, this death sentence! What are you going to do, not even try to hang on, and get washed out of the boat? Accidentally walk over the edge of a cliff? What?”

She looked up brightly. “Jessie, you still don’t understand. I can do my best. I can be cheerful. I can try to be a better person than I ever have before. I just have to be ready for a transition, that’s all.”

I took her by both wrists and looked her in the eye. “Star, I tell you what: I’m keeping an eye on you. You aren’t going anywhere without me.”

“I want you to remember me, Jessie, whenever you hear the song of the canyon wren. That’s going to be me singing, singing just for you.”

“No way,” I said. “A canyon wren is a canyon wren. That’s what I believe. I want you to be you. I think you’re really great, Star.”

She smiled painfully. “Thanks for the vote of confidence. I really appreciate it.”

“Star, you’re . . . you’re like a sister to me, the sister I never had. . . .”

“Same here, Jessie,” she said dreamily. “I know. These days . . . despite everything . . . they’re the best of my life.”

My eyes filled with tears.

“It’s okay, Jessie, don’t feel sorry for me. Let’s get some sleep.”

Star snuggled down into her sleeping bag and fell silent.

In the morning it was cloudier yet: A thicker layer had come in under the high clouds as we slept. I ate my breakfast ration, my one packet of hot cereal, in the general silence. It was going to be a chilly day, and we were in for three Big Drops, as I remembered them from the river guide. Granite Falls, Hermit, and Crystal. Maybe it wasn’t a coincidence that the worst rapids were found in the most sinister-looking stretches of the canyon. I looked up and down the river at the black walls, and I remembered for a moment the friendly reds and whites of the cliffs in the upper canyon. I remembered the amber hue of Freddy’s miracle fountain, the sipapuni by the River of Blue. Gone are the days, I thought. So long gone that our frolic in the sun seemed a distant memory. As I looked up and down the gorge at the tortured black rock, Star’s premonition came to mind, and a chill ran through me.

“A penny for your thoughts,” Troy said. “Join you for breakfast, such as it is?”

“Sure,” I said. I was pleased to have the company. And his blue eyes were warm again, steady. His beard growing in, blond peppered with red, accentuated the old charm that had returned to his smile.

“Well?” he said.

“Just wondering what the day will bring.”

“I love river-running, Jessie, I really love it. I love moving water. I love running this big water more than anything I can remember.”

“More than surfing?”

He smiled broadly. “I can’t knock surfing, but these waves, they’re something else.”

“You haven’t flipped yet—haven’t had any trouble at all.”

“Where’s some wood?” he asked with a laugh, and lunged for a piece of driftwood, almost spilling his oatmeal. “I’m knockin’ on it, I’m knockin’.”

I was laughing too, and then I was hearing something strange, not having any idea at first what it might be. Pug and Adam were yelling and pointing. It was the unmistakable chop-chop-chop of a helicopter. I looked up to see two of them buzzing down the gorge.

We all stood silent for a moment as they flew past, only a couple hundred feet above the water, right down the middle of the gorge. The sound ricocheting off the walls was unbelievably loud. We could see the helmeted men inside looking at us.

“They’re after us!” Adam shouted. “The plot thickens!”

“Where’s my rocket launcher?” Pug thundered. “Oh, for a couple of Stinger missiles!”

“My, my,” Troy said softly, standing next to me. “No place for them to land, is there? That’s too bad.”

City of Gold

City of Gold Kokopelli's Flute

Kokopelli's Flute Take Me to the River

Take Me to the River Jackie's Wild Seattle

Jackie's Wild Seattle The Maze

The Maze Ghost Canoe

Ghost Canoe Never Say Die

Never Say Die Down the Yukon

Down the Yukon Bearstone

Bearstone Beardance

Beardance Jason's Gold

Jason's Gold Far North

Far North The Big Wander

The Big Wander River Thunder

River Thunder Downriver

Downriver Go Big or Go Home

Go Big or Go Home Leaving Protection

Leaving Protection Wild Man Island

Wild Man Island